An Appeal

We have decided to acquire our own domain name for the Lokayata blog, the recurring cost of which will be around Rs 3000 per year. This will help us reach more people. In view of the public-facing nature of our blog, we think it would only be fit if this expenditure is borne jointly by the members of the Study Circle and the general public — our readers, that is you. In that way, it will be easier for us to remain accountable, and you to remain informed. Please note that this is not the creation of a paywall by other means. Your contribution will be discretionary and your access to whatever we publish, either here or on the blog, will remain unfettered. Whatever we do as a Study Circle is a voluntary collective effort and it will always remain that way. Since we are reaching the milestone of the 50th blog post in July — the outcome of our/your perseverance over the last four and a half years and an ode to the intellectual communion which, we believe, has been mutually nourishing — we thought that we should seek your support at this juncture. We are not asking you to compensate us for our time and labour, but to help us access a technological resource that is required for the blog to become an archive of our work and times. It is a small step, but a necessary one. If you like our politically informed critical analysis, our translations from Indian languages, our ground-up reports, or the rare texts that we revisit and publish occasionally, we ask you to contribute whatever little you can and claim the blog as yours too. A Letter in solidarity with Library Genesis and Sci-Hub starts with the following passage:

In Antoine de Saint Exupéry's tale the Little Prince meets a businessman who accumulates stars with the sole purpose of being able to buy more stars. The Little Prince is perplexed. He owns only a flower, which he waters every day. Three volcanoes, which he cleans every week. "It is of some use to my volcanoes, and it is of some use to my flower, that I own them," he says, "but you are of no use to the stars that you own".

It was written by a collective of online custodians. We are asking you to become the co-custodians of Lokayata with us. We are asking you to water the flowers and clean the volcanoes.

What we are reading and looking forward to read

‘Living cruelly’ can serve as a perfect aphorism for Umesh Solanki's report on the haplessness of Adivasis cleaning sewers in Gujarat's Dahej. It records the unreported deaths of three Adivasi men, and the narrow escape of two other ‘lucky survivors’ as they descended down a gutter without any protective gear. It is a grim portrayal of the darker side of a country washed in the waves of neoliberal globalisation — where laws exist as parchment guarantees, and the brutalizing occupation of manual scavenging serves as the sole ticket out of poverty for a good number of people.

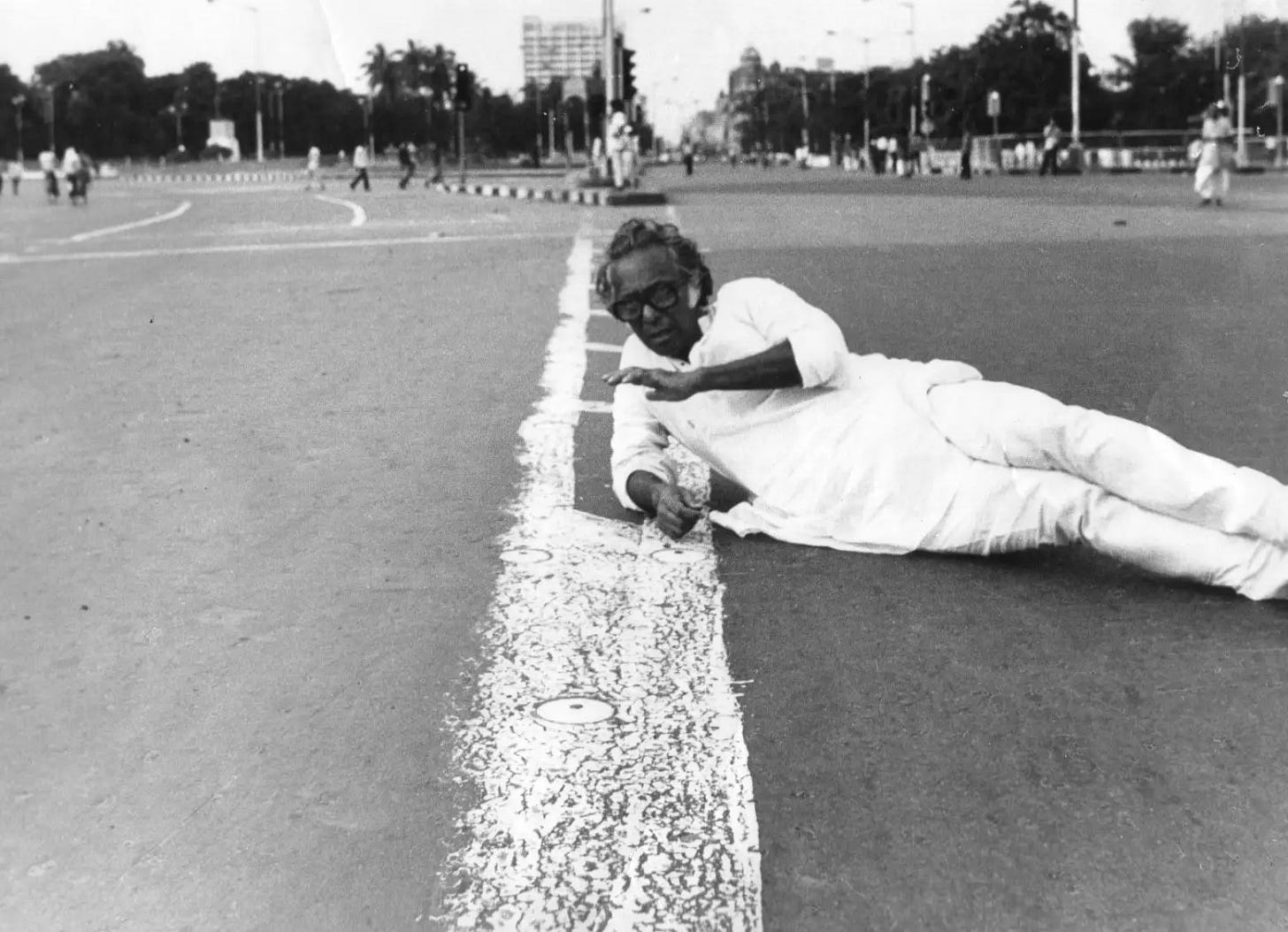

His inimitable style of filmmaking made him a rebel of his own kind. This excerpt from his memoir Always Being Born showcases Mrinal Sen in his most natural habitat, Calcutta. The words are direct, and the reader cannot expect to gain any snuggery from his prose. He recalls his experiences of incessant addas in the Paradise Cafe of Bhowanipore, where he was accompanied by some of the other giants of the contemporary Bengali cultural scene: Ritwik Ghatak, Tapas Sen, Salil Chowdhury and so on. He goes on to refer to the oft-cited debate on the art of filmmaking between himself and Satyajit Ray on the pages of The Statesman. In spite (or perhaps because) of all the bustle, Calcutta remained his muse and inspiration for building a new society, where hunger and exploitation would be words of the past. His own people, speaking his own tongue, filled his frames and thoughts. Most importantly, he dared to dream and to work towards fulfilling it. The broader left movement lacks exactly this today: dreams and actions.

In this captivating exposition, Lily Lynch, a writer and journalist based in Belgrade, demonstrates how an imperialist and forever-belligerent military alliance like NATO has managed to ensnare the European left by cunningly deploying the ideology of wokeness. She begins this piece by citing a press conference of NATO’s Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg with Angelina Jolie. Earlier, these two had penned an opinion piece for The Guardian entitled ‘Why NATO must defend women's rights’. The pair had made the case for increased NATO intervention, ostensibly to end sexual violence in war zones: ‘Ending gender-based violence is a vital issue of peace and security, as well as social justice. NATO can be a leader in this effort.’ Lynch argues that the timing of the write-up was significant: At the height of the #MeToo movement, the intent was to effectively efface the belligerent, pro-war nature of NATO and present it as a progressive, peaceful alliance committed to eliminating gender-based violence across the globe.

She proceeds to ruminate on the arguments proffered by A.M. Wright and Annika Bergman Rosamond. According to them, this press conference with Angelina Jolie was part of NATO's greater strategic narrative in many ways. It imbued the otherwise banal and unremarkable military alliance with celebrity glamour, thus reaching apolitical audiences who have little to no knowledge of it. Furthermore, it allowed the NATO to exploit the ideals of women's rights, feminism, human rights, etc. that usually resonate within left-leaning circles. Essentially, NATO leverages the woke ideology to manufacture consent among European leftists. As Kuss writes, the attempt is not to impose NATO on society, but rather ‘to integrate it into entertainment, education, and civic life more broadly.’ Lynch argues that the European Left has fallen prey to this progressive circus. Major left-wing political parties — with the German Greens leading the way — have cast aside long-held ideals of military neutrality and now lend full support to NATO. With literally no opposition left in Europe, the cultural hegemony of NATO is now absolute.

We look forward to reading The Dark: Selected Writings of Brendan Hughes edited and introduced by Roisin Dubh, and The Palestine Laboratory: How Israel Exports the Technology of Occupation Around the World by Antony Lowenstein.

What we are listening to and watching

Christopher Hill recollects his journey from being a young aspiring cricketer for the Yorkshire county team to becoming a notable Marxist historian of 17th century England. By the end of this televised appearance, he provokes his listener into asking several questions — what is the explicit Marxist contribution to history-writing? Looking beyond the humongous economic tables and charts on agrarian production relations, Hill suggests that it is only possible for a Marxist to look at the whole of the society — that is to augment together the radical desires of what he elsewhere had called the ‘lunatic fringe’ with the designs of those at the highest echelons of power. He leaves us with a lesson, which is no less profound in its scope. No matter the pessimism reigning around us, we must always remain optimistic about the enormous radical potential of the people — something he had learnt from John Bunyan, who was writing in the aftermath of the failed revolution in England.

Recorded in a year of ‘El Proceso’ (the military dictatorial rule over Argentina from 1976 to 1983) – the following interview provides glimpses into the mind of a writer and his strife with ideas — public and private — in the midst of political churn. For instance, is writing enough or does the writer need to be an active political agent during times of injustice? Is execution kinder than being imprisoned? Does the construct of the nation-state make much sense while identifying oneself and one’s literary craft, or is there a category of ‘world literature’ that is independent of the former? An interview of Jorge Luis Borges, the Argentine poet, essayist and short-story writer whose works became twentieth-century classics is being heard by the Study Circle this month. Borges redefines the genealogy that writers shape (he mentions the influence of Kafka, on re-reading Hawthorne) in not only crafting their own independent work, but that they use to redefine the work of other writers and the readers’ understanding of them. In a garland of beautiful commentaries, he warns the writer regarding a priori demands made on their craft and the lure of didactic restrictions one can walk into while writing. As the Study Circle itself enters the last phase of a much-anticipated translation project — Borges reiterates the significance of the English, a language we offer all our writings in — a medium simple yet subtle, operating at the seams of the twin linguistic registers of the Germanic and the Latin.

Tholpavakoothu is a ritualistic art form performed in front of the Bhagvati Temple or Bhadrakali’s sacred groves in central Kerala, in the districts of Palakkad, Malappuram, and Thrissur. Preserved by the Pulavar community, it is a rare and distinct art form that is dedicated to Goddess Bhadrakali, the mother-deity of the region. Performed through the months of January to May, it requires a constructed theatre space known as koothumadam and tells the story of Kamba Ramayana. Originating in the 9th Century CE, this form is being nurtured by master puppeteers like Padmashree Ramachandra Pulavar, featured in this PARI documentary called ‘Tales from the Shadows’ (2023). The Pulavars were said to be bards or storytellers who accompanied the peasants in bullock carts and spread the tales from the epics, by puppeteering. It is said that Lord Shiva wrote 12126 verses of the Kamba Ramayana for his daughter, out of which only a third is performed. The torch is carried by the carpenter community and the sacred cloth (ayappudava, worn by the Goddess) is wrapped around the performers as a symbol of expertise, friendship and reverence. Nonagenarians like Ponnuswami Pulavar are still carrying on with the practice, even though the scholarly and philosophical discussions around this art form are getting lost with the passage of time. The younger generation is reluctant to carry the legacy forward and the impact of COVID-19 had also reduced the number of people attending public performances significantly. Tholpavakoothu, nevertheless, has always had its arms open for all castes, unlike dances like Kathakali which could only be performed inside the temple spaces of Namboodiri Brahmins. This documentary brings to us this theatrical form, pronouncing the loss of deeper meanings and the need to preserve the rich philosophical reserves surrounding it for a longer time, especially for posterity.

What’s cooking in the Study Circle

I had first read this short story by Yashpal in 2014, and it was through it that I learnt that sorrow and grief, which I understood as undesirable, as emotions to be avoided, were in fact a need. A need that not everyone was provided with the means to fulfil. The idea of seeing grief as a right was so new that it left an indelible mark on me. I started translating the story in 2020, during the pandemic, when death and its fear was omnipresent. I could not complete it then. The anxious atmosphere due to the suddenly imposed lockdown did not allow me to. Fear and uncertainty had mixed with helplessness and guilt at feeling limited in helping those whose experiences were far worse.

‘Dukh ka Adhikar’ portrays the struggle of a mother following the untimely death of her young son. The story shows how the urgency of survival for the underprivileged is made more difficult by the norms and codes of the upper castes and classes. Yashpal provokes one to reflect on the material consequences of death, rather than its abstract religious connotations. He carefully lays out details to critique the ritualistic paraphernalia surrounding death, which seem to profit the Bajajs and Lalajis of the town, the same upper-caste people whose understanding of the mother's situation is limited by their ruthless appraisal of her actions. The story highlights the discrepancy in the treatment of death and the ability to mourn it across different classes. This piece was supposed to be finished and published sometime in the pandemic, as a reflection on the disparities within our collective experience of a difficult period. However, it is being brought out now, in an attempt to remember that time. We are still unsure about the ways in which we could remember and mourn, let alone faithfully document the enormity of the pain and loss that people suffered then and the multiple possibilities of life that were erased.

Riya Lohia translates a short story by Yashpal for the Lokayata blog. This month, we read Michael Parenti’s ‘Friendly Feudalism: The Tibet Myth’, a copy of which is available on our blog now. We hope to acquire our own domain name for the Lokayata blog in July, before the publication of our 50th blog post.

What we are thinking about

We are thinking about the state of literary study in academia, particularly that of English Literature. In his 2017 book Literary Criticism: A Concise Political History, Joseph North offers a different history of Anglo-American literary study from how it is usually narrated. Traditional accounts of the discipline’s history identify the ‘theory wars’ of the 1970s and 1980s as its decisive turning point. North argues instead that its trajectory was determined at a deeper level by the pressures of neoliberalism faced by the university as a whole. He shows how these pressures shaped the character of the work produced in literature departments. As they became geared towards producing more and more sophisticated culture analyses, the discipline as a whole shifted away from engagement with popular cultural and educational life and became sequestered inside the academy. Its relationship with broad-based programmes of educational and cultural enhancement, including school education, was replaced by the increasingly professionalised agenda of knowledge production, measured primarily in terms of publication metrics.

North’s analysis resonates with what we know of the present state of the global academia. English, in particular, has been a discipline marked by an uncertain status ever since its inception in the nineteenth century. In India, its indeterminate status has been especially pronounced. It was both an instrument of the erstwhile colonial bureaucracy and the medium through which generations of Indians forged a new literary-cultural sphere. Moreover, as far as literary scholarship is concerned, English departments in India have gone beyond English to produce work on literature in the Indian languages. They have been the site of some of the most insightful discussions on Indian literature, with translation playing a key role in this relationship. This led Aijaz Ahmad to suggest, in his essay ‘Indian Literature’: Notes towards the Definition of a Category, an institutional arrangement for these departments that would allow them to work more concertedly on Indian literature. Ahmad, like North, critiques the increasing professionalization of the discipline. Whereas it was common for the English professor to earlier also be a creative writer in their own right, the discipline now pushed them to simply be a specialist ‘ploughing their own field’. In the thirty years since this essay appeared, even as damning a picture as this has given way to something worse – the dismantling of the university altogether.

Concerns about the specific disciplinary status of English might seem secondary in a context in which the existence of higher education as a whole is in question. Yet, interrogating the nature of the discipline, its complex history and internal contradictions, is relevant to the very idea of the university. If one is arguing in favour of the public university, making claims on public resources on its behalf, it is important to think about what it is that the university contributes to the commons. This is not to conform to the neoliberal demand for providing an economic rationale for every item of public spending. It is rather to oppose this worldview, which construes all value in solely economic terms at the expense of human well-being and to prompt a general self-reflexive practice, which would be sensitive to the social implications of the project of literary study as a whole. An initiative that has interested us, in this context, is the Literary Activism project. The writer Amit Chaudhuri, who founded this project, contends that it has tried to move beyond the dichotomy created between the literary marketplace and the academy, to carve out an alternative space for discussing literature, opposed to the language supplied by the publishing industry and the professionalised register employed by academia. Here, at the Study Circle, we are interested in learning more about endeavours which engage with the literary — which bring together a nuanced literary sensibility and reflections on popular cultural life. We look forward to hearing from our readers and potential contributors to our blog, Lokayata, on this subject.

Who we are remembering

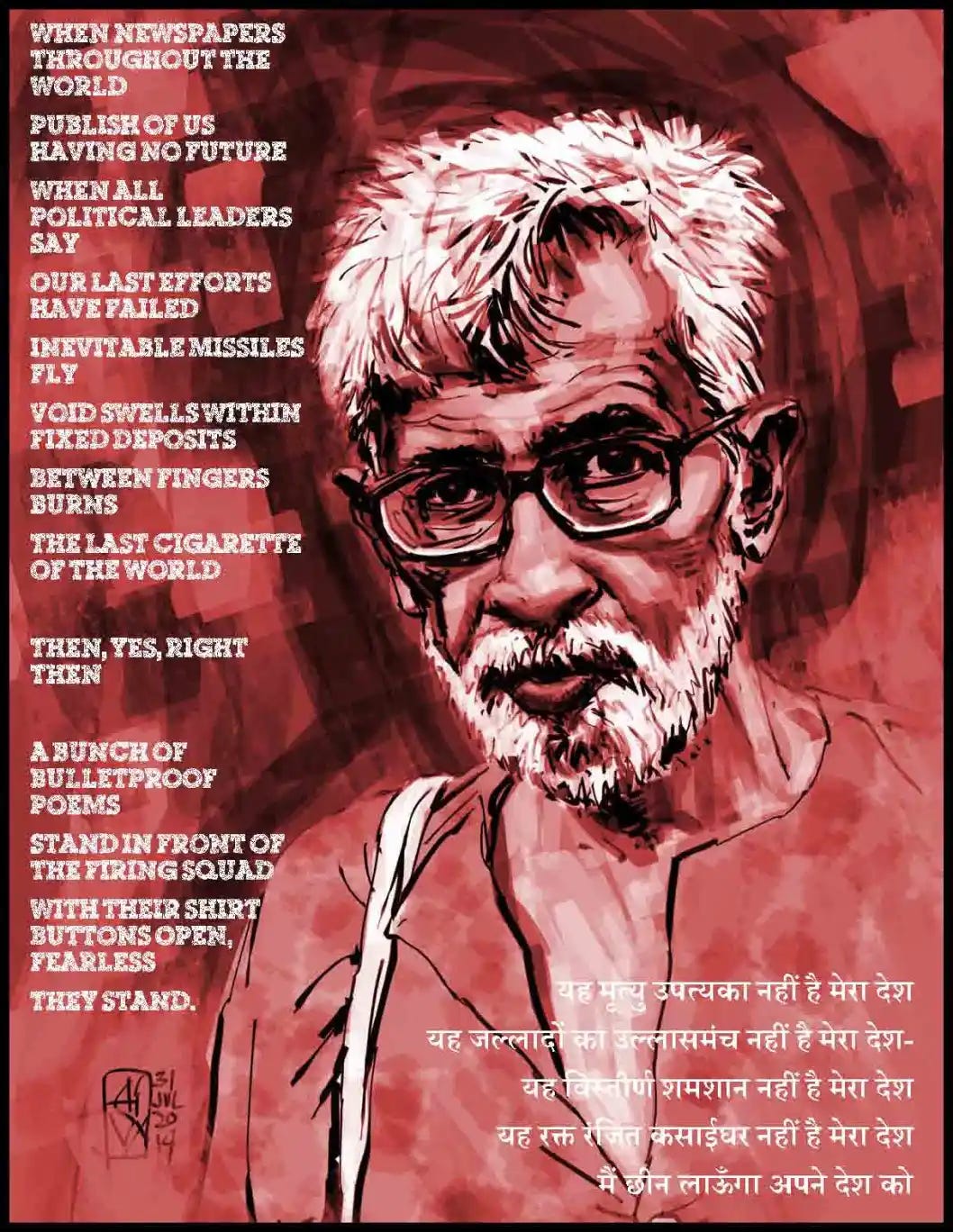

This month, we are remembering the genre-defying rebel poet and firebrand Bengali author Nabarun Bhattacharya. Read a bit about his background and his philosophy of literature here, and one of his immortal poems, translated from the Bangla, here.

That’s all from us for now. Let us know what you thought about this newsletter in comments or over email.