What we are thinking about

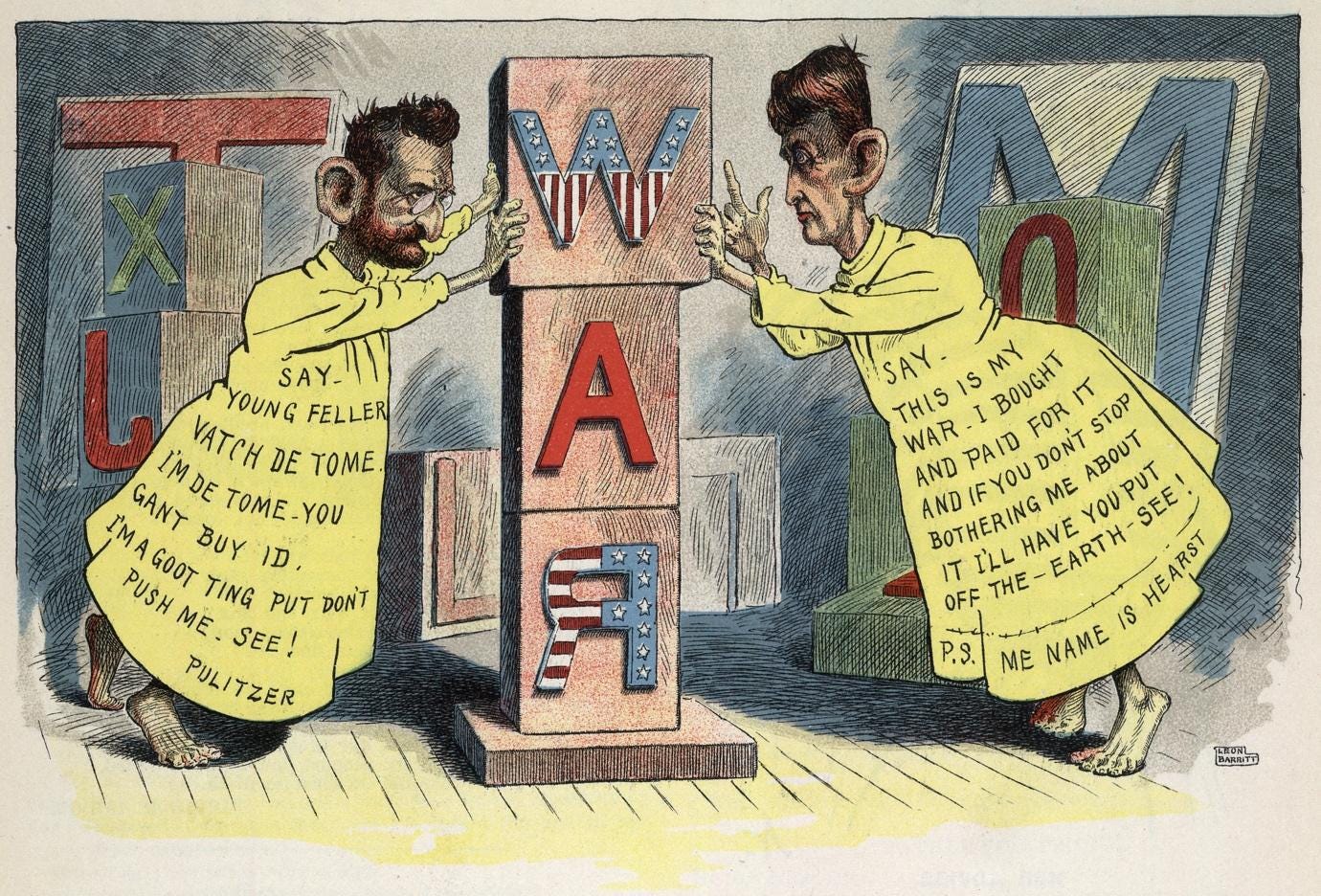

In 1898, the USA went to war with the Spanish Empire, cheered on by William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer. The apparent casus belli for the war was the sinking of the USS Maine off the Havana harbour — an event blown out of all proportions by Hearst’s New York Journal and Pulitzer’s New York World, and immediately attributed to the Spanish without much regard for incriminating evidence. This ‘splendid little war’ as it came to be known, was as much the handiwork of the newspaper proprietors as it was of the US Government. Pulitzer and Hearst competed with each other in reckless reporting, sensationalizing war news, floating conspiracy theories, disregarding and obscuring actual evidence, and engaged in relentless self-promotion to claim credit for victory in a war whose outcome was touted since even before it began. These newspapers were not just in the business of manufacturing consent, they were interested in manufacturing wars.

Pulitzer and Hearst were piggybacking on an ideology called nationalism, but their own interests were more pecuniary: they were trying to make money through a coordinated disinformation campaign — perhaps the most consequential if not the first of its kind — ever since instantaneous reporting on armed conflicts had come in vogue during the Crimean War (1853-1856). Pulitzer and Hearst’s brand of journalism — decried as the ‘yellow press’ in their own lifetimes — seems to have been rehabilitated, and is even celebrated as the most appropriate business model today. Journalism has become a great distraction and honest journalism a liability for the big print, television, and digital media corporations. They are solely interested in generating advertising revenue by auctioning off readers’ and viewers’ ‘attention capita’ to the highest bidder.

While delivering the third Usha Mehta Memorial Lecture in 2005, Ashis Nandy had identified three crucial birthmarks of nationalism among several others. First, he asserted that nationalism is predicated on the premise that ‘the state is central to public life, if not to life itself.’ Nationalism has a tendency to monopolize, which is why it ‘fears other identities as potential rivals and subversive presences’ — the second cardinal feature identified by Nandy. Thirdly,

there is ample scope in nationalism for identifying deviants and traitors for with-hunts...Nationalists are always nervous that the nation is not nationalistic enough…the more the nationalists come to love the abstract entity called the nation, the more they dislike the real-life persons and communities that constitute the nation.

What is missing from Nandy’s analysis is what brings all this together. Nationalism is an ideological shroud for the nexus between the state, big capital, and a compliant if not conformist press, which are in a quid pro quo relationship with each other.

The state has outsourced its function of being the pre-eminent vehicle for nationalism to a press bankrolled by and subservient to the interests of big capital. Journalists, these days, are expected to be and take great pride in being nationalists. In India, the media landscape has been so monopolized by this breed that it becomes difficult to tell them apart from the spokespersons of the party in power. It is our great misfortune that instead of embracing this condition gregariously, there are foolish journalists who continue to act against their own interests by refusing to be comforted and cruelly ignoring the gentle nudges of a magnanimous state. They would rather spend time in prisons than in penthouses. Their New York counterparts, however, have responded to the call of Pulitzer and Hearst well. Having egged the USA on in almost all of its illegal and secret wars abroad, they have now willingly contributed to a global McCarthyite witch hunt. After all, good nationalists must get rid of witches and traitors. Senator McCarthy and his followers stood strong against Un-American activities back in their time. New York journalists must continue to follow his lead now — by ensuring that all traitors in India are forever banished to that anti-nation called Tihar in our own times.

What we are reading and looking forward to read

2023 Nobel Peace Prize Winner Nargis Mohammadi’s book White Torture: Interviews With Iranian Women Prisoners was translated by Amir Rezanezhad in 2022. In this book, the author documents the stories of several captive women like Zahra Zahtabchi, Sima Kiani, Marzieh Amiri and Fatemah Mohammadi, recording their accounts of torture and abuse by the prison authorities. Arrested for the twelfth time and sentenced to solitary confinement for the release of this book, Mohammadi stands upright as a representative for women’s rights, as a campaigner against death penalty, as Vice President of the National Council for Peace as well as Defenders of Human Rights Center (DHRC). The incarceration and torture inflicted on the political prisoners are aimed to crush them as families, into total isolation and socio-economic exclusion. She defines ‘white torture’ as the deprivation of ‘all sensory stimulation over long periods’, applicable for prisoners of conscience and state prisoners alike. As per the reports of 2020, convictions against freedom of expression have increased by a massive 52.9%, while an unprecedented 89% increase is witnessed against unions. The author talks about intentional torture, where there is no unbiased court or a relief from detention. Living with no contact with their families or children, the ‘only way to get out of the cell was confession, repentance and cooperation’ — responses valued by the regime. Drugged, blindfolded, and sexually abused, Nigara Afsharzadeh recalls the horrible dealings with loneliness: “When they brought me lunch, I would chop up the lumps of rice and throw them on the ground to attract an ant or something else”. The book remains an example of daring and painful recollection, one which can neither be escaped from, nor forgotten.

“We don’t have anything And y’know you go out less and less before at least you went to the store to buy food went to the post office I mean you’ve never liked going on walks I have always loved to go on walks Before yah before I met you I always went on long walks Every Sunday I went on a walk And other days too And I had friends maybe not a ton of friends but I had friends girlfriends But they they never really come here…”

The Nobel Prize in literature this year went to Jon Fosse for his ‘innovative plays and prose which give voice to the unsayable’. In a small excerpt from ‘Night Sings Its Songs’ we find how this unsayable might have to do with the institution of a family, its rapid change in contemporary times — where both capital and unemployment increasingly define intimate human relations. This has bearings on not just the old and young generations, but also generations that follow (the new-born child in the Fossian background, is always present but never on the stage). The family, in its ties intimate and beyond, has definitive bearings on the way the larger community of nations are shaped and how individuals identify with each other in the mundanity of everyday. Also interesting to note is the usage/translation of the singular word ‘Yah’ = Norwegian ‘Ja’ into American ‘yes’. The same word appears repetitively in the select piece, but everytime with a new tone/meaning — yes, so, well, yep, hmm, OK, fine, oh, sure, yeah, uh-huh, tsk, ugh… This has implications on not merely the nuance of this said piece but also the larger problem of translation and accessibility, its politics that pedestals a certain work over the other in the global labyrinth of knowledge production — shaped by nations — not always reflective of a necessary genius.

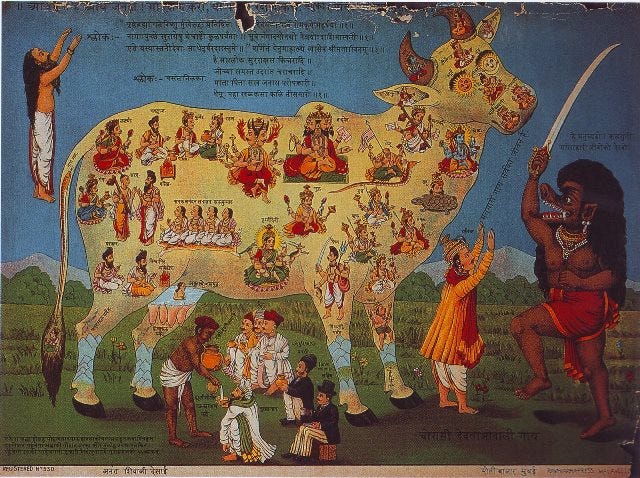

In India, calendar art has been a very important component of popular culture. It has had a very crucial role in the formation of beliefs and values that are prevalent in contemporary India. In this article, Baisali Mohanty, ruminates on how the cow grew into being a sacrosanct symbol of Hinduism. This article was written in the wake of lynchings related to beef-eating in India. Manohar Lal Khattar, the chief minister of Haryana, famously said that Muslims could live in India only if they gave up eating the meat of cows, for the cow is an article of faith. Mohanty argues that this perception of the divine cow was created through calendar art. In the post-colonial polity, cow was envisioned as a unifying strand in Indian life, cutting across class, caste and the rural-urban divide. All the Hindu gods (in some instances, also Sikh Gurus) were assimilated in the body of the cow, and as a result thereof, the cow became a new object of worship unto itself. Later on, this would provide impetus to the cow-protectionist movement in India. Towards the end, she asserts that in order to counter the hatred pushed by Hindutva, there should be a counter-propagation of plurality and multi-culturalism.

In this 2021 article, Ravinder Kaur writes about the role played by big capital in branding India in a Hindu nationalist image. The economic deregulation of the 1990s led many commentators to envision a dilution of national identities in favour of a more fluid, global identity. Yet, the nation-state went on to be reconceptualised in a different way. On the one hand, India abandoned the ‘Swadeshi’ ethos that had guided its nationlism through much of the twentieth century, and began marketing itself as a haven for foreign investment. On the other hand, this marketing harnessed an image of India's ‘cultural uniquiness’ that had been constructed by the Hindutva movement. Through a brief analysis of this public relations regime, Kaur shows how the image of this ‘brand-new nation’ has been created through the hollowing of a democratic ideal of nationhood

This month we are looking forward to read Keeping Up the Good Fight: From the Emergency to the Present Day and Knowledge as Commons: Towards Inclusive Science and Technology by Prabir Purkayastha.

What we are listening to and watching

The history of the emergence of the Indian nation-state out of its colonial past has mostly been discussed in terms of failure — not one, but several. The misfortune of averting the partition of the subcontinent was pinned upon the failure of the people of the nation to come together. Henceforth, unity was sought in the post-colonial polity — industrial modernity was accepted as the way forward for the same. People on the Left, specifically those associated with the communist movement of the day, were painting a very different picture. Beneath the edifice of half-baked capitalist modernity lay buried the age-old prejudices of caste discrimination that could only lead to eventual pauperisation of the downtrodden. Films like Subornorekha (The Golden Thread) would depict the underside of this nation-making process. Yet, while doing so, the directors like Ritwik would imagine their version of the nation — one that would ultimately manage to break free from its own past. In his celebrated text On the Cultural Front, he writes that this can only be achieved through the re-interpretation of our ‘national heritage’. To do the same, the artist would have to bring forth the consciousness of the collective.

Edward Said recollects his contentious memory of his homeland — a place he could barely enjoy. His experience as a Palestinian Christian reminds us that the struggle for Palestinian liberation is a national question and not a religious one. In this documentary, he draws parallels between the Western Zionist project and the conquest of the New World. According to him, the Zionist movement encapsulates the imagination of the Western world because the element of setting out to build a new state on a tabula rasa, much akin to that of a phoenix, is engraved in a Western ethos. Said opens up for us a new avenue to reflect on this settler-colonial project which is predominantly European and white — something that did not consider the plight of Asian dark skinned Jews.

We leave you with a montage of Palestine from a time when the British empire was yet to redraw the boundaries of the Middle East to serve its own geopolitical and economic interests.

What’s cooking in the Study Circle

While the detrimental consequences of overconsumption must be acknowledged, one should not be tempted into unduly apportioning the blame for this to individuals alone. We should also consider the relentless onslaught of advertisements in manufacturing desire and artificial needs, and by extension, creating a culture where both demand and supply are exponentially increased. Contrary to the dominant view that increased production is only a response to people’s increasing needs, production and consumption are mutually reinforcing. In order to continue amassing wealth, the producers must cultivate willing consumers for their products. A perpetually-ready consumer base is ensured by closely tying the well-being and happiness of individuals to consumption. Thus, the more they consume, the happier they purportedly become. Essentially therefore, overconsumption should also be treated as an ideology — an ideology that seeks to obfuscate the role of capitalism in perpetuating a vicious cycle that leads to endless accumulation of wealth for a select few by pinning the blame on individuals.

The Marxist philosopher Mark Fisher coined the term ‘magical voluntarism’ to describe the undue emphasis assigned to individual decisions as a means to deflect attention from addressing systemic questions. For him, magical voluntarism is “the dominant ideology and the unofficial religion of contemporary capitalist societies.” In order to properly grasp the nuances of the politics of climate change, it must be understood as a complex interplay of individual agency and broader systemic forces. Individual decisions by themselves cannot properly address the structural problems embedded in capitalist societies today. Moreover, this is not as simple as raising public awareness about ecological concerns. When a fossil fuel company encourages awareness campaigns through advertisements that foreground the individual responsibility to save the planet, it is at best hypocritical and deflectionary.

Read Shashi Singh’s piece here as he categorically breaks down the faux-emphasis on overpopulation as a driving force behind climate change. In this month's reading session, we will discuss Marxism and the National Question (Chapters 1 and 2) by Joseph Stalin. Our project to translate Rahul Sankrityayan’s Dimagi Gulami is continuing apace. In a meeting held last month with some of the translators, we discussed the various exigencies associated with the act of translating, editing, and annotating a text so temporally remote from us, yet so acutely relevant. These ruminations, along with those of the editors, will find home in a detailed note, as one of the appendices of the book. We are working closely with the finished manuscript, and hope to finish our work with all the possible appendices (featuring a biography, a bibliography, a commemorative essay, and original correspondence) by the end of November latest. Last month, we had received an overwhelming number of applications for the membership of our Study Circle. We have inducted four of the applicants through a two-stage process — Hira, Srestha, Shirshendu and Yanis. With new members on board, we aspire to take up several new projects with fresh enthusiasm and renewed zeal.

Who we are remembering

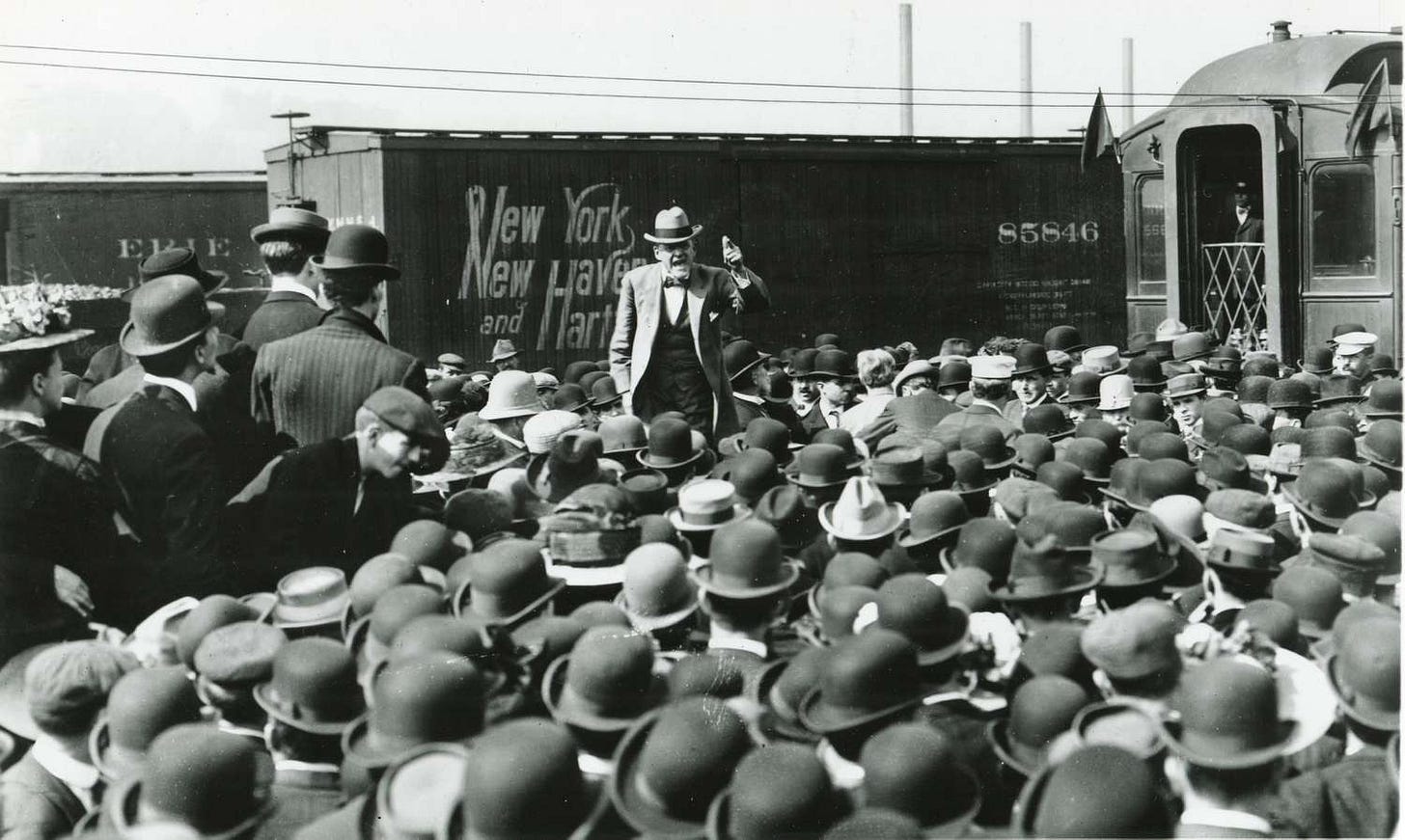

This month, we remember one of the foremost socialist thinker and practitioners born in the United States — Eugene V. Debs, who passed away on the 20th of this month in 1926. Read more about him here.

That’s all from us for now. Let us know what you thought about this newsletter in comments or over email.