What we are reading and looking forward to read

The past several weeks have been incredibly eventful. Our thoughts are with the flood-affected victims in Pakistan, who are facing what has been called a ‘monsoon on steroids’. Residents of the lacustrine city of Bangalore in India have recently experienced intense flooding as well. Natural triggers are not the only reasons behind these environmental tragedies. As the Tricontinental Institute for Social Research’s 15th Red Alert notes,

[S]corching months resulted in abnormal melting of [Pakistan’s] northern glaciers, whose waters met the torrential rain spurred by a ‘triple dip’—three consecutive years of La Niña cooling in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. In addition, catastrophic climate change—driven by global carbon-fuelled capitalism—has also caused the glacial melt and downpour.

[…] Significantly, the impact of the rising waters on Pakistan’s population is due to unchecked deforestation and deteriorated infrastructure such as dams, canals, and other channels to contain water.

That the ‘global south’ is disproportionately vulnerable to the rapidly unfolding yet terribly under-reported climate crisis is widely known. What is not so well-recognized is the predatory role of Bretton Woods institutions like the IMF and the World Bank, which do intervene in humanitarian catastrophes such as these, but with their own interests in mind and with lots of strings attached—usually in the form of prescribed austerity measures.

At the height of the pandemic, Damian Barr’s quote, ‘We are all in the same storm. Some of us are on super-yachts. Some have just the one oar.’ had made the headlines. It holds true when we talk about the climate crisis as well. Even within the global south, the most vulnerable communities are those that literally inhabit the margins, littoral and riverine. Their stories are not always about suffering and deprivation, but of resilience and solidarity too. Siwjee Singh Yadav, the headmaster of the only primary school in Dabli Chapori NC, a shifting sandbank island in the middle of the Brahmaputra river in Assam’s Majuli district is a figure who embodies both qualities. He is almost singlehandedly responsible for the education of all 6-12 year olds on that unsurveyed island. Read about his gritty and flood-defying work here.

While we are on the subject of education, it seems only fitting to plug Shiv Visvanathan’s rich opinion piece here. It showcases the systematic destruction of the public university space in India, and its transformation from a ‘state of being’ to a monotonous technocratic service centre. He argues that the concept of ‘collegiality’ or learning together, which used to be a cornerstone of the university system, is slated to see a gradual erosion as a result of the bulldozing of the Indian higher education landscape with the new National Education Policy. The joy of learning through debating and deliberating upon conflicting ideas, with the university space being a crucial facilitator of such discussions, seems to be a thing of the past. Visvanathan underscores the sadness that a condition such as this entails, with education being reduced to mere commodities for sale, and with students rendered into passive consumers.

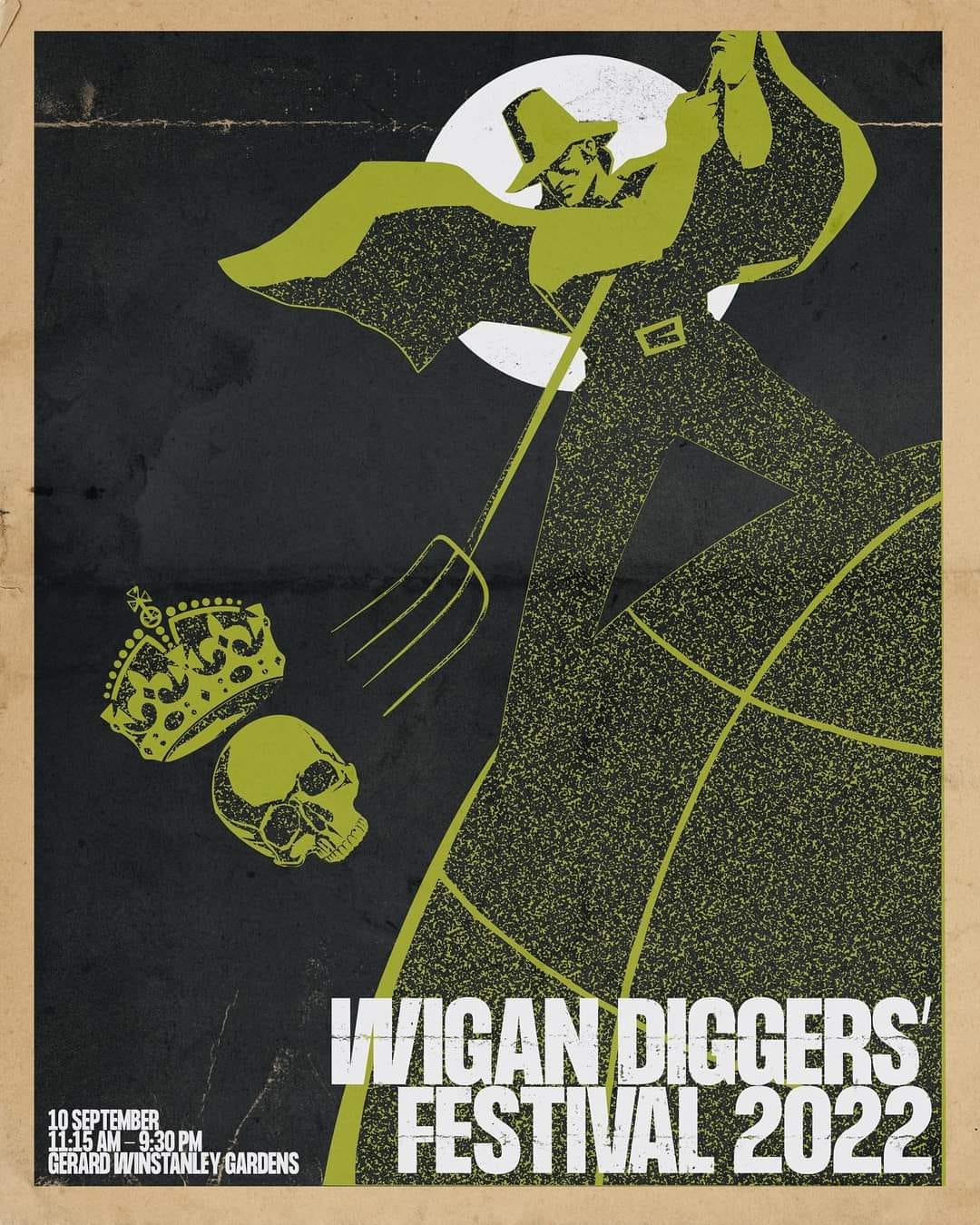

In other news, the death of Elizabeth Windsor, ‘Queen’ of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland seems to have captivated many, and raised several questions about the nature and relevance of the British monarchy at the same time. We found John Rees’ article for Counterfire extremely helpful in navigating the labyrinthine networks of power and privilege, landed estates and feudal titles, extra-parliamentary influence and a largely loyal mass media, that underpin the anachronistic political scaffolding known as the ‘House of Windsor’—formerly the ‘House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha’. Rees doesn’t mince words in his concluding remarks:

There is likely to be a crisis of confidence, if not a constitutional crisis when the Queen is succeeded by Charles. It will be a moment when ordinary citizens in the UK have to examine whether an hereditary, hugely wealthy, unconstitutionally influential, politically reactionary institution is still the best adornment of a supposedly democratic society in the 21st century.

We look forward to reading three books: N. Sukumar’s Caste Discrimination and Exclusion in Indian Universities: A Critical Reflection, Sushmita Pati’s Properties of Rent: Community, Capital and Politics in Globalising Delhi, and Karthick Ram Manoharan’s Periyar: A Study in Political Atheism. Read more about Periyar’s emancipatory politics and the uses of his fiery rhetoric in this old Study Circle article.

What we are listening to and watching

True to our constant concern about the ongoing climate crisis on planet Earth, we decided to give this debate between between Jason Hickel and Sam Fankhauser a watch. Prof Hickel demystified ‘degrowth’, arguing that the term itself is a misnomer. As a normative concept, it is very context-specific and certainly not a Luddite response. Simply put, it is ‘the planned reduction of of socially less necessary production in rich countries in a just and equitable manner.’ Poorer countries still dependent on carbon emissions can continue to grow, as must sectors such as renewable energy, and the incomes of working classes across the world. ‘Degrowth’ policies prescribe constraints only for the overconsuming few, who also wield disproportionate power in economic decision-making within the paradigm of global capitalism. ‘Green growth’, like other promises of neoliberalism is not just unjust and tone-deaf but also paints a patently false picture of the crisis we are inhabiting today and the ecological precipice we are headed towards. We were convinced by Hickel, let us know if you are too.

We have also been watching this short documentary featuring the resilient people of Baro and their philosophy of FOLI, which means that everything in the world is rhythmic. It is tied to conviction in living harmoniously with nature and its many sounds. The everyday lives of the people of Baro foreground an alternative worldview that is so different from the realities that dominate our present.

We think that you might find this documentary on the ‘other 9/11’—the CIA-backed coup against the democratically elected socialist government of President Salvador Allende in Chile by General Augusto Pinochet—interesting. At a time when memories of this crime are sought to be erased from public discourse and when the current Chilean President Gabriel Boric’s attempt to replace the Pinochet-era constitution has been recently upset, ‘How to Make a Nation Scream’ is an essential watch.

What’s cooking in the Study Circle

The Study Circle in its recent meeting decided to invite membership applications from those interested in joining the collective. Prospective applicants must fill out this form by September 24 to be considered for election: https://forms.gle/VoUPdQtBCJVctfTi7. We are thinking of inducting two to three new members who will bring fresh ideas and new initiatives on the table, so go ahead and apply and do spread the word!

The Lokayata Blog has come out with a brand new article by Ananyo Chakraborty on the politics of 'sensory heritage' and why socio-economic contexts need to be woven into any story of 'cultural loss' in a growing urbanscape. Ananyo writes:

'The organizers of the exhibition clearly demonstrated how these ‘artefacts’ are gradually disappearing from the city but did not try to really probe why it was happening in the first place […]

The story of cultural loss of olden sights, sounds, and smells is also a story of political and economic displacement and dispossession of people involved in such occupations. The aestheticized presentation of the ‘artefacts of sensory heritage’ somewhat makes us forget that behind the sound of every street vendor’s cry is a working person of flesh and bones, living with their daily struggles and socio-economic exploitation under a semi-feudal and semi-capitalist order. Such poor workers, who have been involved in traditional occupations for years, are rendered unemployable due to changes in the socio-economic structures and are then compelled to work for less in more informalized sectors.'

Do check it out and share if you like it!

What we are thinking about

In contrast to terms like ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy’, ‘justice’ has historically elicited a far wider gamut of understandings and manifestations across epistemological and political contexts. Etymologically derived from the Latin word iūstitia—meaning righteousness—it was in the ancient and tumultuous times of Athenian democracy smarting from the defeat to Sparta that Plato sought, in a didactic and dialogic fashion, to provide an answer to the question of what it means to live a just life. Integrating personal moral enhancement with a rigid functional specialization among social classes, many tenets of Platonic justice might be out of sync with our current sensibilities. Nevertheless, the enduring, and often elusive search for an uncontested meaning of justice continues. The twentieth century witnessed the germination of the Rawlsian scheme of liberal egalitarianism and also the sowing of the seeds of neoliberal justice by Robert Nozick and F.A. Hayek amidst the reign of the intuitive idea of giving what is due to each. Beyond the admirable intellectual exercise of expanding the horizons and dimensions of justice, all these strands of thought shrouded an underbelly of a more fundamental injustice—embedded in the histories of colonialism and unbridled capitalism.

The Indian Constitution gives preambular expression to justice in the social, economic, and political spheres. Aiming at lofty goals such as the abolition of economically privileged classes and achieving equal terms of political participation, justice in its constitutional avatar served as the theoretical justification of the Nehruvian state-led developmental model. The concrete policy imperatives on the other hand were deftly kept in perpetual abeyance by consigning them to the unenforceable section of Directive Principles. The birth of the Indian Constitution coincided with the rumblings of resistance across the axes of language, caste, economic exploitation. In fact, these bore an interesting resemblance with the trajectory of the anti-colonial struggle, where the popular movement led by the Congress ran in tandem, and sometimes in tension, with upheavals by the revolutionaries and the communists.

As the years wore by, justice came to be weaponized as an articulation of ‘historical grievances’ to justify communally charged visceral projects of Hindutva like the Ram Janmabhoomi movement, laying bare the subjective understanding of ‘justice’ mis-shaped by passion and political skullduggery, and shorn of rationality and fairness. Today, as Bilkis Bano watches her convicted rapists walk out of jail and embraced gleefully, one cannot help but take note of the blatant inversion of justice enabled by an ever-growing gap between procedural law as administered by the courts with all its loopholes, and the substantive notions of truth, fairness, and moral integrity. While the majoritarian motif suffuses all public institutions in the country and courts dither on and delay the settling of crucial questions concerning civil liberties, one is reminded of the popular maxim that justice must not only be done but also seen to be done. As the values and promises of the Constitution that we cherish are all undone bit by bit, the resuscitation of something resembling the idea of justice in the Indian polity is something that we all long to see.

Who we are remembering

Julius Fučík was a Czech journalist, literary critic, and member of the Communist Party who was deeply involved in the anti-Nazi resistance during the Second World War. He saved the lives of his numerous comrades by giving false information to his captors who tortured and eventually executed him. Read his Notes from the Gallows here.

That’s all from us for now. Let us know what you thought about this newsletter in comments or over email.