Seventeenth Newsletter - December 2023

Ruminations and Recommendations for our Readers.

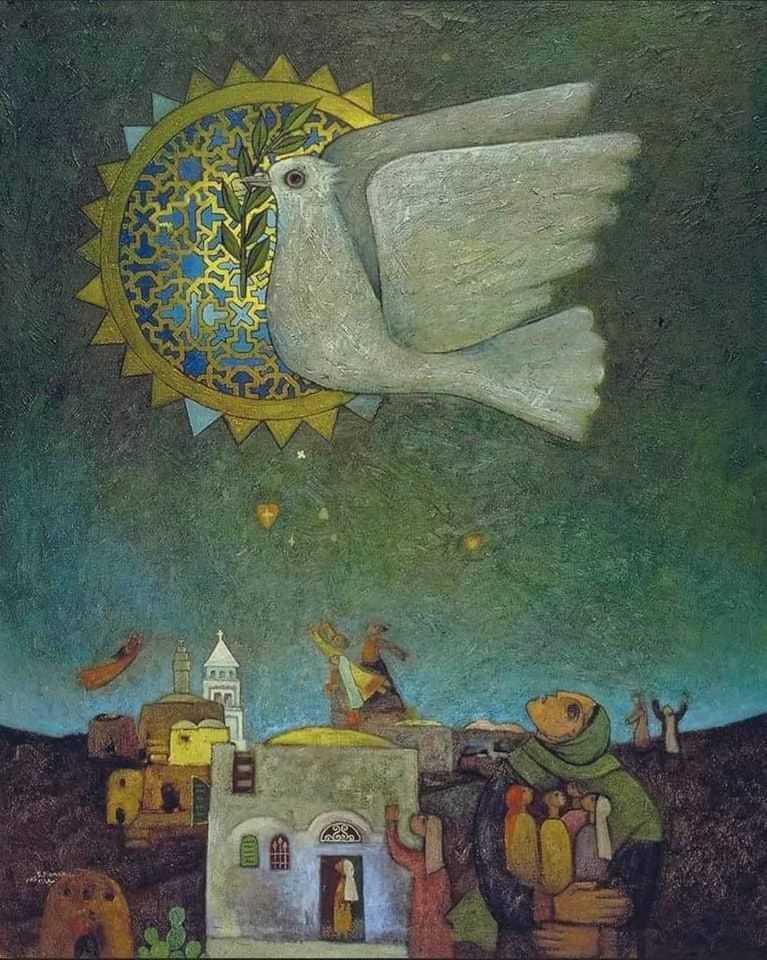

Requiem

This was a year of war and atrocities. This was a year of silence. This year was. We hope that the coming year will not be so shadowed. We hope that it will bring solace and peace. We still hope. For what it’s worth, hope is contagious and conspiratorial. Like spring, it swells up from under the ground, catching even the most adroit gardener off guard. When hope becomes a little more than hope, we call it resolve. We hope the world wakes up and finally resolves to end the occupation of Palestine.

What we are thinking about

In a recent incident, eight ad-hoc teachers were displaced from the Ramjas English Department, a college which is one of the constituent institutions of the Delhi University. Important here to note is how the college predates the University. Three other colleges, namely St. Stephen’s College (1881), Hindu College (1899) and the Zakir Hussain or the erstwhile Delhi College (1792) predate and in turn constitute the university itself. While this has legal, economic and other connotations, the fact of the matter is that DU is a collegiate university and it is the undergraduate departments of the constituent and affiliated colleges, their many courses, that attract students from all over the country. For a century now, the University has produced doyens in different fields of life, from different colleges. The same ethos is captured in an anthology edited by a current Union Minister. The pertinent question then arises— will this record of 100 glorious years as celebrated by the minister simply be a thing of the past?

The answer seems to be a resounding yes! We have already established how various college departments shape the existence of the University. For a century now, college departments of the University of Delhi have produced academics who have rewritten the way their disciplines have shaped up. But wait, there is a twist to this story! Behold the categories ‘Ad-hoc’ Professors and ‘Guest’ Lecturers. To teach in an Indian University, one needs to have met a certain set of minimum eligibility requirements. However, there are provisions for making temporary appointments against permanent vacancies to ensure the smooth conduct of classes until a panel can be constituted to interview suitable candidates for the faculty position. This was supposed to be an extraordinary measure, a stop-gap arrangement so to say.

Over time, this became institutionalised as permanent appointments dried up. By the end of the second decade of this century, as many as half of all the college teachers in DU were ‘ad-hocs’ or ‘guests’. There are many obvious benefits of making such appointments for the university authorities. The appointer does not have to pay social security. The appointer gets to hire and fire on a monthly-drawn contract. The appointer extracts the same amount of work on half (and at times quarter) the pay. The appointer never gets to hear a ‘no’ to any arbitrary work as the appointee is under a constant fear of a non-renewal. However, there is only one loss that this system generates. A mutilated academic: overburdened, overworked, underpaid and a slave of the system. What scholarship or erudition can such an individual produce? We will, perhaps, only have Samarveers.

As the system now expunges these ad-hocs who have survived decades of ghastly lives to sustain whatever remained of a university that has become a shadow of its past self, more than individual losses, the story of ‘ad-hocs’ is one of necrosis — of the very spirit and rationality that came from the college departments and their scholarship, in grafting the idea we now nostalgically call, and draw an identity from, our beloved and almost dead, University of Delhi.

What we are reading and looking forward to read

In this article, the philosopher Christopher Michael Cloos reviews James Rachels’ objections to the concept of ‘Cultural Relativism’ in the sixth episode of ‘Exploring Ethics’ series. Its proposition is that no universal truth can be fundamental to all cultures of the world and that moral restrictions against wrongful acts like stealing, arson or genocide are only relative. Cloos navigates the key commitments of this concept, highlighting the practice of killing infants and sharing wives, common amongst Inuits or Eskimos of Arctic Canada and the USA. The socially determined correctness in one society is alien as a moral code in another. If we believe in burying our dead and paying respect to them, another person may eat or feed their dead people to do the same. Cultural Relativism is often seen as a contributor to inter-cultural tolerance and greater possibilities of coexistence. Opinions keep on changing and render the conditions of the world unstable. So, we might as well ask, in this ‘great chain of being’, can we be sure about our affirmations and ideologies? The answer is relative.

This month we are reading the 46th Newsletter of the Tricontinental Institute for Social Research which illustrates how liberal democracy has not been able to successfully curtail the rise of the far right. It posits that while liberal elites dislike the far right’s extreme views, they redirect people from class-based politics to a politics of hopelessness, similar to that of the far right, which in turn is quite comfortable with the established institutions of liberal democracy. The main criticism of the far right comes not from liberal institutions but from grassroots movements, in fields and factories.

Rudrangshu Mukherjee comments on the works of a historian who has always been castigated to the fringes of the traditions of his own belonging. Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, despite being a very well known name amongst the medievalists of Europe; could seldom make a cut amongst the most celebrated of the Annales school historians. Mukherjee brings to light a larger body of work which transcends the trope that is most-associated with him — that of a demographic historian. Ladurie tried to see through the anonymous masses to narrate the accounts of individuals who constitute the abstract category of the ‘mass’ itself. In other words, Ladurie through his later works, provides much food for thought when it comes to writing histories of individuals — not of citizen this or citizen that — but of “people who loved, married, lied or committed other transgressions.”

We are looking forward to read The Oxford Handbook of Caste by Surinder S. Jodhka and Jules Naudet and The King’s Plunder, The King’s Bodies: Prize laws, the British Empire and the Modern Legal Order by Rahul Govind.

What we are listening to and watching

Mike Dibb does a brilliant job in bringing to life C.L.R. James's celebrated autobiography that recounts his relationship with cricket. The sport completed what C.L.R. James would refer to as a very British upbringing. While recounting his own experiences as a cricketer of some merit, C.L.R. James takes a deep dive down into colonial and post colonial politics in the Carribbean. He simultaneously unearths the ordering of the Victorian society through the disciplining regime of cricket — something that would also educate the British colonies to be at the beck and call of the home country. Yet C.L.R. James's story of the sport is not a theoretical one. His tale is prosaic with the likes of W.G Grace, Learie Constantine, Neville Cardus and Frank Worrell featuring as towering demi-gods. His language and Mike's visuals do justice to the elegance of the sport — as they also try to answer Tolstoy's favourite question — what is art?

This month, we watched the 1985 Soviet anti-war film Come and See by Elen Kilmov. The plot revolves around a Belarusian partisan named Flyora, who joins the resistance forces against his mother's wishes. Using a mix of hyper-realism and surrealism, Kilmov paints a ghastly picture of war — one that not only leaves behind a devastated country but also renders all its participants dehumanised and depersonalised. We watch this movie against the backdrop of the barbarous invasion of Gaza by Israel. The film serves as a graphic reminder of the material realities of war — especially when fought between two absolutely incomparable beligerents. Miseries unleashed are untold, but above all — the victims and the perpetrators, are left alienated from its outcomes.

What’s cooking in the Study Circle

Alienation cannot be combated by treating the self as a source of spiritual power that resists corruption by all ‘external’ forces. Rather, we need to understand that individuals are, in fact, powerless under capitalism. There is no reservoir of divine meaning that remains unaffected by the market. All of us are constituted by capital. Tracing the history of the capitalist society and its contradictions and weaknesses is the only way to overthrow it. By deflating the spiritualist view of the world as driven by an innately meaningful story, Marxism enables us to observe how undemocratic and exploitative processes determine our lives.

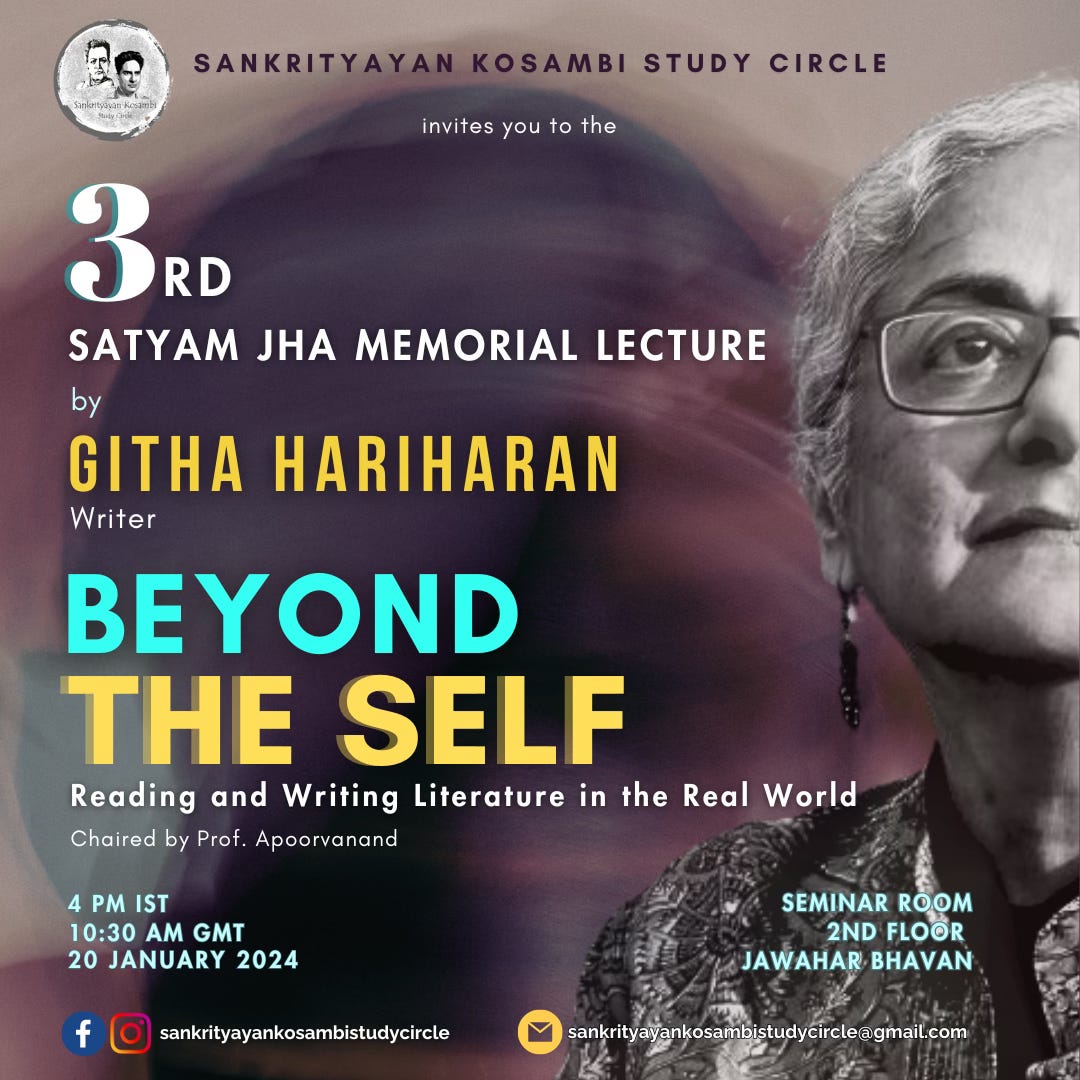

Read here, Yanis Iqbal’s take on the crisis of alienation and the myth of a meaningful life under neoliberal capitalism. In other news, the third Satyam Jha Memorial Lecture will be delivered by Githa Hariharan on the 20th of January at 4PM IST in the seminar room (second floor) of Jawahar Bhavan, Delhi. Prof. Apoorvanand will preside. We hope that you will be able to join us either in person or online from our Facebook Page.

Who we are remembering

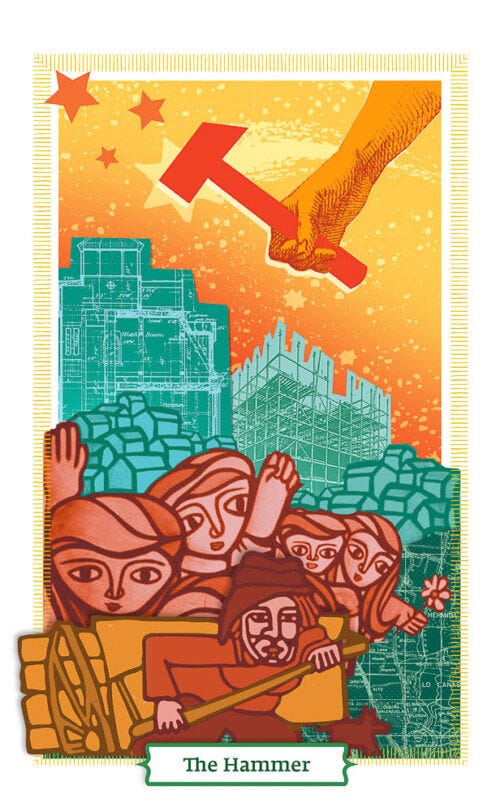

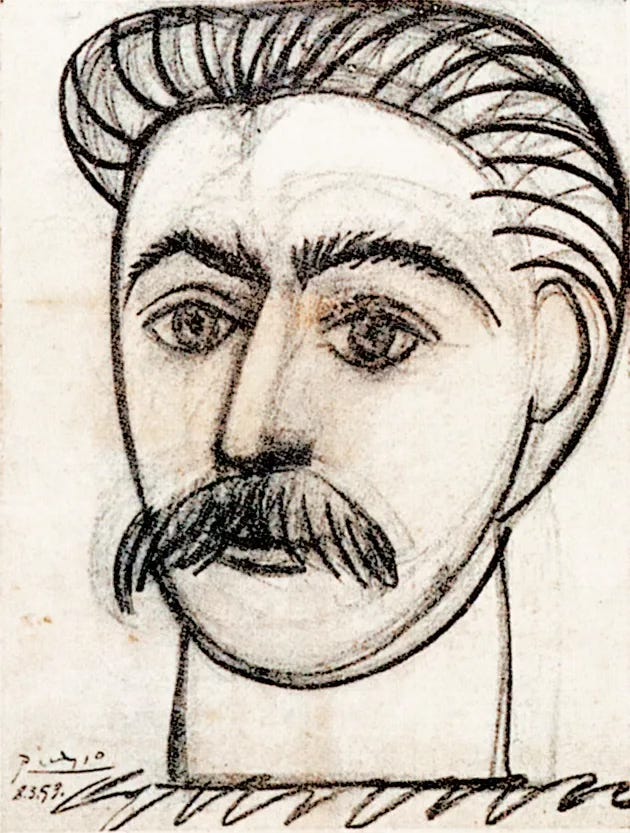

This month we are remembering Joseph Stalin whose date of birth is often contested between the 18th and the 21st of December. We commemorate his contributions to the practice of socialist state-building, internationalism, peace movements, and his leadership during the war against Fascism. Read more about him, here.