Seventh Newsletter - February 2023

Ruminations and Recommendations for our Readers.

What we are reading and looking forward to read.

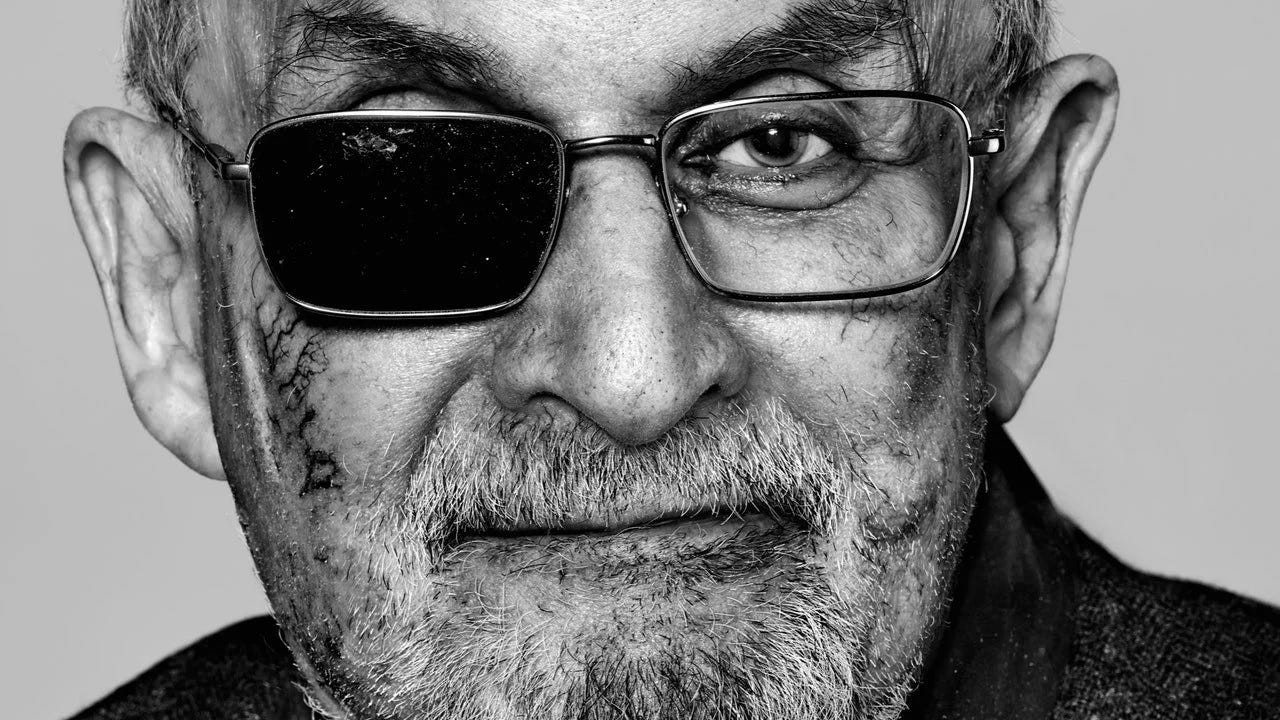

In a rather Socratic turn of events, Salman Rushdie was stabbed multiple times at the Chautauqua Institution in New York, where he was invited to deliver a public lecture on August 12, 2022. Following six weeks of hospitalization and subsequent recovery that left him blind in one eye, Rushdie regains his ground by proclaiming writing as a ‘death-defying act’. Aged 75 and still with a bounty on his head, the author refuses to be terrorized, let alone believe in ‘absolute security’ in a world that doesn’t allow his fiction to speak louder than his truth. This incident compelled us to revisit John Milton’s Areopagitica, a pamphlet originally published in 1644, that served as a torchbearer for protests against state censorship and licensing mandates in the Parliament of England. Milton asserted that the defence of falsehood is an underestimation of the power of truth (or, truth to power). In a similar vein, Rushdie too emphasizes that the very act of writing (as performance) itself has taught him to ‘behave as if (he was) not scared’. Freedom of imagination and freedom from fear go hand in hand, as does skepticism, satire and the ‘defence of the unholy glee’, or what Andrew Martino calls ‘the freedom to offend’. We strongly condemn every violent assault on artists and writers and hope to find leaders who aspire to become better readers, remembering what Kundera noted: ‘hate traps us by binding us too tightly to our adversary’. Today, it is important to not only demand the freedom of literature and literary endeavours, but to also encourage an atmosphere of debate, dissent, and a moral commitment towards creating spaces conducive to voices of resistance and rectitude.

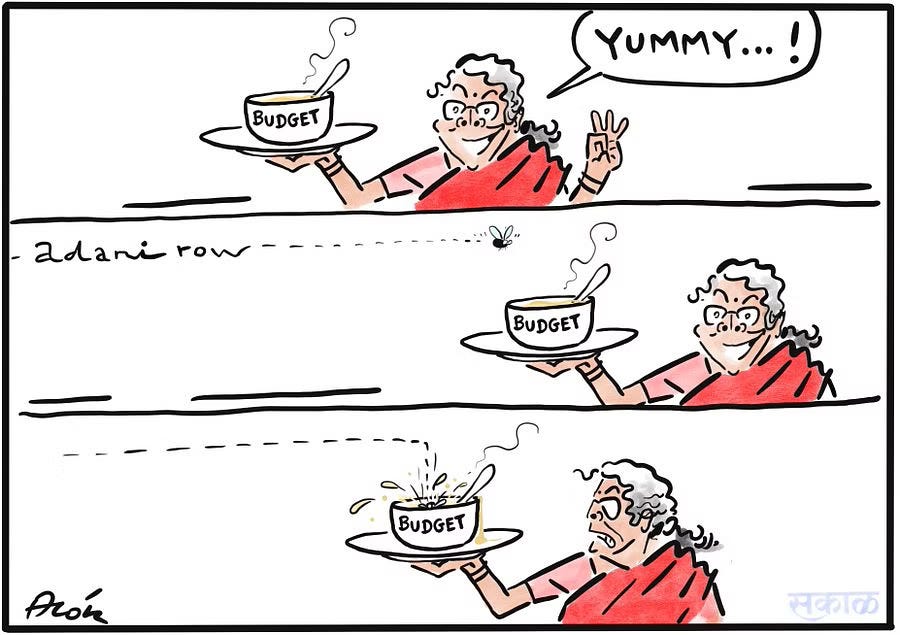

February is an important month. Some associate it with love, some with revolution. Much of India, however, awaits the first of February with bated breath as it happens to be the day when the Annual Union Budget is presented. Nirmala Sitharaman, the Finance Minister of a nation whose economy has been in ruts from even before the pandemic, read out the budget this year from a ‘digital bahi khata’. The irony of history is that the bahi khata of the moneylender/landlord was among the first symbols of oppression, that the Indian peasant burnt prolifically during their many anti-colonial uprisings. Briefcase to bahi khata transition notwithstanding, this year, the Parliament was rife with slogans alluding to an Adani-Modi crony nexus. This detailed analysis of Indian big business and its hand-in-glove dealings with the union government and the ruling party by Jairus Banaji exposes a systematic quid pro quo proximity, making one wonder, who this economy is really for:

“The systemic, long-term nexus between the political elites and big business will not go away anytime soon,” wrote journalist M. K. Venu in 2015. Writing in the aftermath of Obama’s second visit to India, Venu suggested that “crony capitalism” had to be grasped in a deeper sense to reflect not the odd favors bestowed on this or that industrialist by the government of the day, but the system that cemented the ties between state and capital. In this case, it was a handful of family-owned businesses that knew they could always depend on India’s governing class, starting with the prime minister. Venu cited a revealing example of this bond. “At the Modi-Obama reception at Rashtrapati Bhawan [on Sunday 25, 2015], about two dozen industrialists had been invited and were seen standing in a queue to greet the US president. About six to eight of those present collectively owe close to Rs. 3.5 lakh crore to banks, mostly public sector undertaking (PSU) banks. The banking industry in India has about Rs.5 lakh crore as total capital and nearly 70 percent of it is exposed to just a half a dozen industrial houses. Technically, if these business houses were to go bust, 70 percent of India’s banking capital will get wiped out. In short, they are too big to fail. So they have no worries really, as the system sustains them.”

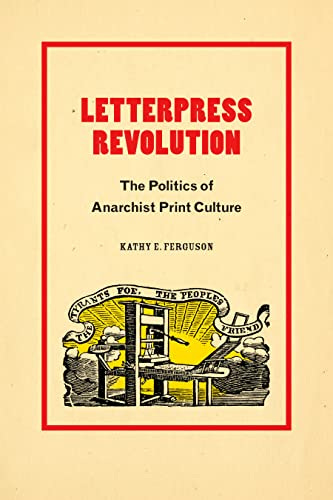

We look forward to reading two new books: Letterpress Revolution: The Politics of Anarchist Print Culture by Kathy E. Ferguson, and The Capital Order: How Economists Invented Austerity and Paved the Way to Fascism by Clara E. Mattei.

What we are listening to and watching

This month we were listening to two lectures by Anupam Guha. Across these lectures, he delves into a fundamental question that the world of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has often deliberately failed to raise or answer: what is the nature of the datasets and algorithms that are fed into an AI model? Guha argues that the AI does not operate autonomously. Rather, any AI (with its unmatched computational and pattern-matching skills) works on datasets that are manually sourced. Though it is a system that is designed to learn or train itself, he asks the crucial questions—who is producing the algorithms? Who is training the AI? Guha contends that usually governments and tech giants have an absolute monopoly over the choice and content of these datasets. Such a monopoly renders them more powerful than ever. Guha ends on a note of optimism and suggests that the apprehensions regarding the AI can largely be solved if algorithms and datasets are socially owned. Guha makes a case for the open sourcing of AI projects. It is important to note here that OpenAI, whose GPT 13 has captivated the social media with its ability to churn out cogent English prose, is a Microsoft subsidiary, its name notwithstanding. We feel that Guha’s lectures offer a good political introduction into the ethics of AI and its relationship with human labour for our own times.

The Enlightenment-era dichotomy between reason and emotion has often been challenged—encouraging one to view these categories as linked, one being affected by the other. For instance, the cruel images of internal migrants walking hundreds of miles to reach their homes during the COVID-19 pandemic, capture a reality that no statistic can claim to represent in a similar manner before the public eye. In her poem ‘Home’, the British Somalian poet Warsan Shire registers the plight of migrants across time and space—the absolute cruelty of a globalization that has taken place at a tremendous cost, forcing ‘the other’ to migrate from zones of conflict to zones of indistinction. The plight, however, continues and is amplified—as these migrants are never really accepted or assimilated. The persistence of anti-immigrant propaganda in the First World is no news to anybody, but perhaps it is not so foreign to the experiences of internal migrants in the Third World either. Shire’s poetry, with her recital or aawaz not only adds to one’s ‘rational understanding’ of the plight of those who have left their homes behind, but also makes one wonder, in her own words—‘i dont know what i’ve become’!

What’s cooking in the Study Circle

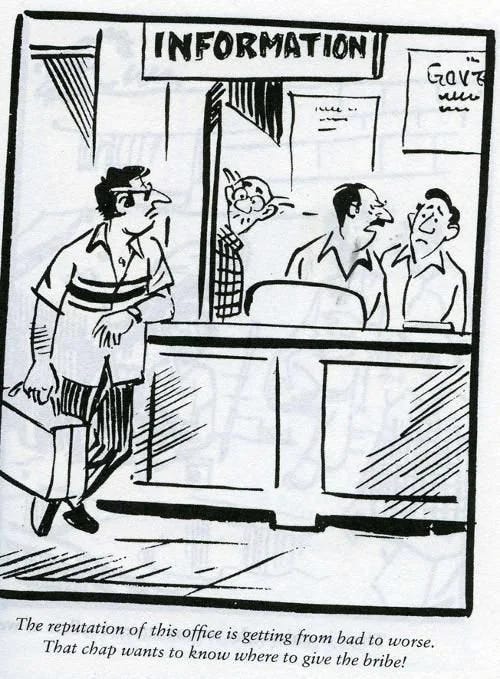

This month has been rather eventful for the Study Circle. In January, we read B.T. Ranadive’s essay ‘Caste, Class and Property Relations’. This month, we discussed Cara Cilano’s book chapter ‘Eternally Displaced Persons’ in our reading session. Both the texts can be downloaded from our blog, as usual. Writing for the Lokayata, Ritabrata Chakraborty explained why we usually turn a blind eye to the pervasive institutionalization of financial corruption in India:

This depicts the grim reality but does little to explain the underlying motivations—and limitations—that drive corruption. While there are generalized explanantia like political culture and lack of education that provide only a broad framework, it is the complete breakdown of the principal-agent relation that, to some extent, explains corruption in the Indian context. In a conventional idea of a democratic structure, both public representatives and officials are agents who convert the political will and mandate of the electorate—who are the principals—into reality. However, behind this cloud of democratic idealism is a steep imbalance—between citizens’ role in actual statecraft and the official conduct of the agents—that loosens public scrutiny and undermines institutions and mechanisms that monitor the self-serving actions of the agents. This, in turn, generates an institutionalized culture that normalizes corruption incrementally. Most people, in despair, give in to the negative consequences and supposed irrationality of swimming against the tide, thereby discouraging a lot of individuals from steadfastly insisting on transparent practices on every occasion. This finally leads to a collective-action phenomenon where there are very few exceptionally ethical persons left in the administration. The expectation of honesty and integrity from government personnel then becomes largely non-existent. The principal-agent relation discussed above is further damaged since the percolation of institutionalized corruption among the people results in a scarcity of ethically-sound principals who can keep a check on the conduct of the state officials. Transfer of responsibility, when imperfectly monitored, therefore causes a sustained erosion of accountability and expectations thereof, amongst all stakeholders.

On Red Books Day 2023, we revisited an old pamphlet (in all probability written by Rajani Palme Dutt) that was first issued by the Communist Party of Great Britain in June 1940, titled ‘The Empire and the War’. This edition of the pamphlet features a preface by Vijay Prashad for context and some reflections towards the end to add more colour. The front cover has been designed by Kadambari. A copy of the pamphlet can be downloaded for free from here.

What we are thinking about

The story of the newsletter goes back to the times when the ancient Romans were thinking critically about questions surrounding state and governance. The Acta Diurna, which has often been recognized as the first gazette in the world, was also akin—in some ways—to the modern newsletter. Written on stone or metal slabs, it contained important official news about events taking place in and around the city. They were short and precise, and were meant for the literate and propertied citizenry. Parallels to the Acta Diurna can be found at many other places in the ancient and the medieval world. However, the word “newsletter" came in vogue only towards the end of the 17th century, against the backdrop of the rise of mercantilism in Western Europe. As Benedict Anderson argues, the development of print capitalism provided an avenue for the integration of the capitalist class, through the timely relay of vital information regarding the prices of various commodities, tariffs, discovery of new trade routes and so on. Constant and accurate knowledge of the markets was necessary for merchant capitalists to tailor their investments accordingly. Daily newsletters—both printed and handwritten—carried information about the fluctuations of the market prices of commodities. They also contained bits on important social and political developments, therefore becoming instruments of capital formation and accumulation. A lot of newsletters, like Benjamin Franklin's Poor Richard's Almanack, served as a medium of advertisement for companies and their products—a role still played predominantly by newsletters of lifestyle brands. For the general public, however, newsletters often became channels for sharing gossip. Most newsletters, by the middle of the 18th century, developed into full-fledged newspapers. However, owing to government crackdowns on dissident publishers, newspapers had to frequently transform themselves into newsletters from time to time. Due to their crisp nature, newsletters readily found readership in underground circles, in cafe discussions between renegades and outliers, thereby (somewhat) subverting their original role as handmaidens of business.

We are currently living amidst a newsletter boom, fuelled primarily by Substack. Several writers across the world have chosen to go independent through newsletters. Not just individual writers, but research institutes and think tanks, leading online news portals, and e-commerce corporations are using this fairly effective method to take their work directly to their intended audience and subscribers. This resurgence of the newsletter is happening in a world much different from that of the sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries. With ‘Reels’ and ‘Shorts’ reigning supreme as the global currency of online ‘content’, attention-spans of readers have been on the decline for a while. Long reads are no longer popular. The target has become largely to feed bit-sized ‘content’ to a largely attention-deficient consumer base. Readers become subscribers bound to their choices, and subscribers are in turn converted into predictable consumers. Consumption becomes further atomized in individual mailboxes, breaking collective solidarities. The Lokayata Newsletter was started as a standalone newsletter in August last year, keeping in mind this concern of receding attention-spans. However, we believe that our readers are not passive consumers of information but active thinkers in their own right. We have therefore decided to provide them with lengthy recommendations and ruminations on topical issues that are capable of stimulating further thought. This is a collective endeavour of the Sankrityayan Kosambi Study Circle, and we attempt to be always true to our objective of promoting critical thought and interdisciplinary studies, complemented by our solidarities with progressive movements across the world. In our very humble effort to audaciously hold ground against the tide of heightened atomization of collective life under a neoliberal onslaught, it is our sincere hope that the Lokayata Newsletter is able to become a small messenger gesturing towards a better future that lies ahead.

Who we are remembering

One of the greatest poets of the twentieth century, Faiz’s poetic forays into the themes of romance and revolution were deeply reflective of his own life. Be it his self-reflective critique of independence (ye daagh daagh ujala, ye shab gazida seher), or his imprisonment by the state of Pakistan (which came down heavily on the then Communist Party), or even his later exile, the beauty of remembering Faiz lies not just in the transcendent nature of his work on the human condition, but also in his elementality and simplicity that reminds one how people are people because of people. He continues to live in those instances where even years after his death, a group of students protesting against a prejudiced Citizenship Act retort against police brutality with 'Hum Dekhenge’. Read more about him here.

That’s all from us for now. Let us know what you thought about this newsletter in comments or over email.