Sixteenth Newsletter - November 2023

Ruminations and Recommendations for our Readers.

What we are thinking about

There has been a global expression of outrage at Israel’s indiscriminate bombing of the Gaza strip, which a number of scholars have now categorised as genocide. While mainstream Western media continues to distort the reality of Gaza in Israel’s favour, it is on social media that people have come together to share information and express solidarity with Palestine. This has created a veritable global community out of people from different parts of the world connecting with each other over their shared outrage at an ongoing genocide. Someone viewing it from India can similarly enter this global community, and many have done so by amplifying Palestinian voices and adding their own voices of support. Yet, for an Indian, engaging with the Palestinian cause has to be more than an expression of global citizenship.

The Indian response must also be located in the Indian political context, which has witnessed a growing alliance between right-wing Hindu nationalism and the settler-colonial ideology of Zionism. While India continues to officially vote for the two-state solution to the conflict and has sent aid supplies to Gaza, its foreign policy has taken a decisive turn in favour of Israel, departing from the decades-long policy of support for the Palestinians. Protests in solidarity with Gaza were clamped down in many places, whereas pro-Israel demonstrations carried out by Hindutva supporters faced no such obstacle. Perhaps, the most grotesque form in which India has been complicit in Israel’s genocide is through the Indian mainstream media’s propagation of fake news supporting Israeli violence.

Therefore, it becomes important for people in India to oppose the genocide not just as fellow human beings but also specifically as Indians. India’s historic support for the Palestinian cause was as important for the latter as it was for India’s own self-identification as a country that stood up for the rights of colonised and oppressed peoples around the world. What it means to be Indian has been contested all through its modern history and rarely more so than today. By standing up for the rights of Palestinians today, we also define what we are as a nation.

Of course, India’s principled stand against colonial oppression around the world never meant that things were ideal back at home. Far from it: India, like Israel, has the distinction of keeping a region and its people under permanent subjugation throughout almost the entirety of its existence as a state, the region in question being Kashmir. This is where India’s particular connection with Israel becomes especially salient. As India and Israel have become partners in subjugation, and even colonisation, the Palestinians and the Kashmiris have found solidarity with each other. As we in India now express solidarity with Palestine, we need to do the same for the Kashmiris.

We would be apt, at the same time, to be terrified at the horrendous scale of the Israeli attack – being described as a second ‘Nakba’ – for another reason. No matter when it ceases, the precedent set by it will have a troubling afterlife. We know that violence tends to breed more violence. Israel, in particular, has turned itself into something of a laboratory for perfecting the technology of colonial oppression. Even when this latest, deadly, wave dies down, the example set by it would probably encourage right-wing governments around the world to enhance their own apparatuses of repression. For us, it could set a particularly dangerous precedent for the persecution not only of Kashmiris but also of minorities across India. In opposing Israel, we need to oppose the technology and logic of violence that it reinforces around the world. In being disturbed by and speaking out against its atrocities, we simultaneously express dissent against ethnocentrism in our own polity. By seeing Gaza as a node in a fabric that stretches across the world, we express a collective humanity that has historically been the most liberating aspect of the global struggle against colonialism in all its forms and guises.

What we are reading and looking forward to read

In April 2022, the Indian-women and Dalit-worker led union TTCU signed a historic agreement with the clothing and textile manufacturer Eastman Exports to end gender-based violence at Eastman factories in Dindigul, Tamil Nadu. TTCU, GLJ-ILRF, and AFWA also signed a legally binding agreement, subject to arbitration, with multinational fashion company H&M. Under the terms of the Dingdigul agreement, brand signatories are obligated to impose business consequences on Eastman Exports if the latter violates its commitments. Together, these interlocking agreements constitute the unprecedented Dindigul Agreement — an “enforceable brand agreement” (EBA) in which multinational companies legally commit to labour and agree to use their supply chain relationships to support a worker- or union-led program at certain factories or worksites. Ankita Dhar Karmakar graphically conveys the historical background for the movement and highlights the effective clauses of this agreement.

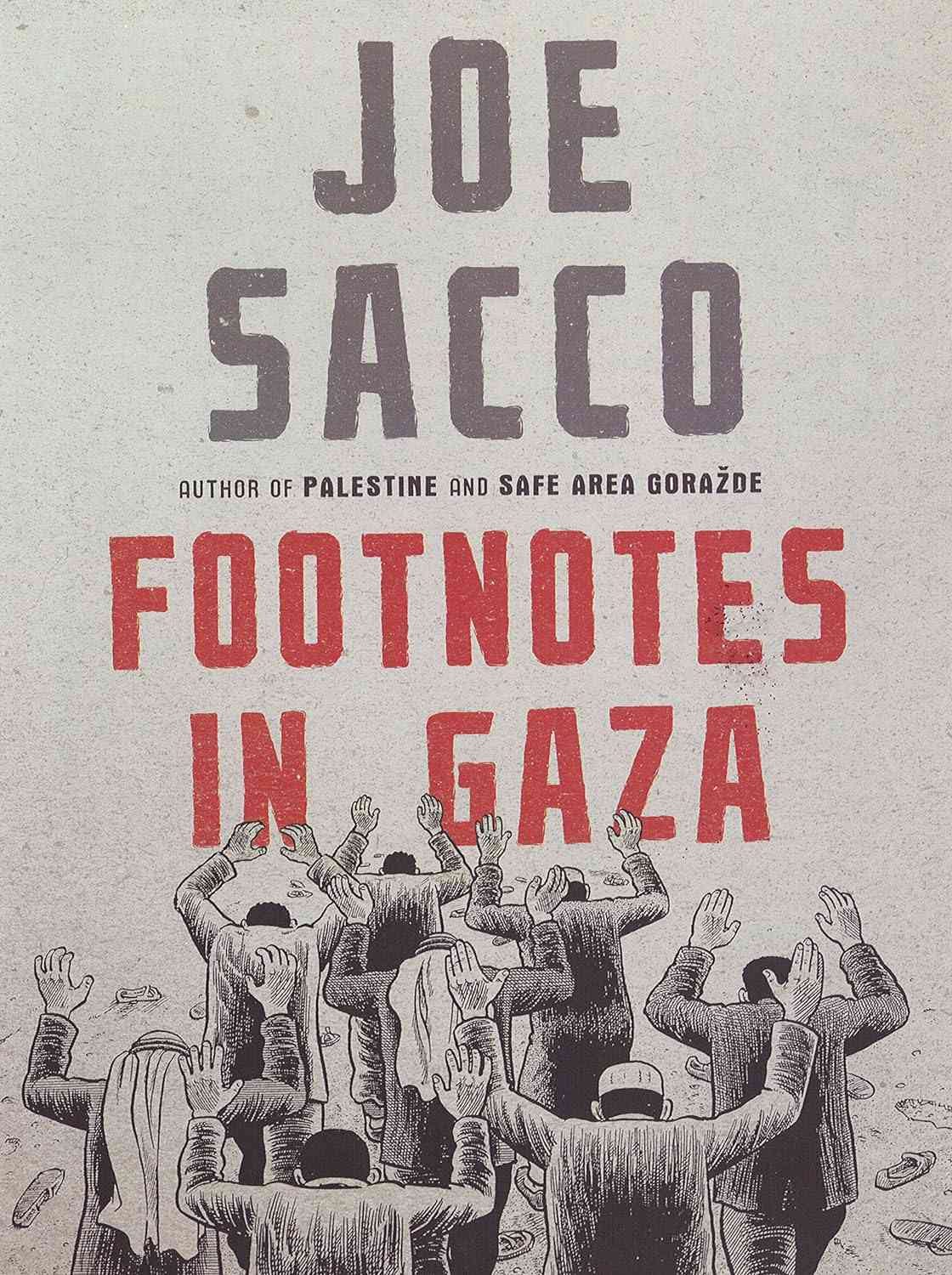

“History chokes on fresh episodes and swallows what footnotes it can.”

In this article, Swati Singh ruminates on the work of Joe Saco, a Maltese-American cartoonist and journalist. Joe illustrates the horrendous events that unfolded in 1956 during the Khan Yunis massacre and argues that these are just ‘a tiny speck on history's canvas’, for there have been countless deaths since then. The large number of Palestinians deaths have been reduced to mere statistics, with entire lives being relegated to footnotes. His evocative illustrations are significant because they not only seek to salvage the ugly reality of Israeli colonialism from disappearing in collective amnesia but also, much to the chagrin of the proponents of ‘bothsidesism’, highlight the inherent power imbalance by means of contrast between the two parties. On one hand, Israelis are shown to have been liberated in a technologically-advanced country— there is claustrophobia on the other, with the Palestinian refugees being confined to a crumbling frame. Most importantly, as Singh highlights, Saco doesn’t pigeonhole people in his work; he rejects easy categories such as terrorists or tragic survivors and imbues Palestinians with the dignity to have agency, aspirations and contesting points of view.

The Palestinian author Adania Shibli contemplates the futility of the written word amidst gigantic events like massacres and genocides that aim to strategically decimate a specific population. Shibli describes her vain attempts at articulating her state of mind after receiving an alarming early morning call from the Israeli Defence Force informing her that her house might be aerially bombed:

But when I try to think of what I could say or write, I’m suddenly paralysed, knowing that the words that will pour out of me will be futile. This realization, that words cannot hold and that they are wholly feeble when I need them the most, is defeating.

In these trying circumstances, her previous life in Berlin, where she wrote in solitude, made little sense. She shifted to Ramallah in Palestine as a visiting faculty to teach students. Her students were used to the violence and experienced the fear of death on a daily basis. She couldn’t express the enormity of the events that were unfolding in front of her eyes or their impact on her students. However, things changed as she saw a sliver of light flickering through the window inside her Berlin house on a solitary night. Away from her home and students, she found hope to write again, since she felt that words “can, for all their smallness, leave a certain trace in the world, as did this faint light emanating from the streetlamps.” It is only after looking at the war from a distance that she could write about how difficult it was to write when she was faced with the threat of communal incineration.

We are looking forward to reading the anthology of short stories Palestine +100: Stories from a Century after the Nakba, edited by Basma Ghalayani, and Decolonising the Palestinian Mind by Haider Eid.

What we are listening to and watching

This month we are listening to a podcast featuring a conversation between Danielle Cybulskie and the historian Natalie Zemon Davis. Davis' work is characterised by a commitment to exploring the lives and experiences of ordinary people, bringing their stories to the forefront of grand historical narratives. Davis' book The Return of Martin Guerre (1983) is a classic example of microhistory, which, through the case of a 16th-century French peasant — who disappeared for several years and was replaced by an imposter — deals with questions of identity-theft at a time of shifting religious loyalties. In her book Trickster Travels: A Sixteenth-Century Muslim Between Worlds (2006), she explores the fascinating life of Hasan al-Wazzan, also known as Leo Africanus. Born in Granada in the late 15th century, Leo Africanus witnessed the fall of Muslim Spain and later travelled extensively throughout North Africa and the Mediterranean. His encounters with different cultures and societies during a time of significant political and cultural shifts make him a compelling figure. Davis uses Africanus' life as a lens to examine the complex interactions between the Islamic and Christian worlds during the Renaissance.

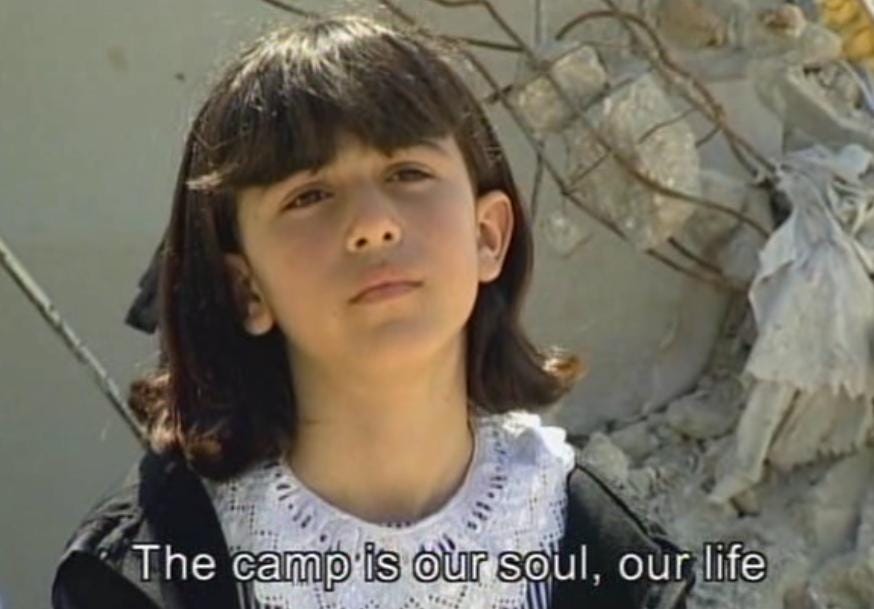

Directed by the renowned Palestinian actor Mohammad Bakri, the film Jenin, Jenin (2002) portrays the ‘Battle of Jenin’ or the massacre at the Jenin refugee camp carried out by the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) in April 2002, in which more than five hundred people were immediately killed using fighter planes and offensive weapons. The film talks about the repeated invasions and constant occupation of the citizens of Jenin through their testimonies, which reveal serious violations of international humanitarian law by Israel. The victims talk about how the USA collaborated with the perpetrators to draw an image of Palestinians as ‘non-democratic, reactionary, underdeveloped and inferior beings’, describing the situation as one worse than Vietnam. As opposed to Israel, where 1000 Jews live in 10000 square kilometers, the population density of Palestine is 13000 per sq. km, which makes the Palestinians vulnerable to attacks and creates a perpetual sense of fear and danger among them. They compare the use of weapons upon them with the insecticides that are sprayed on crops, highlighting how they are stripped of their status as human beings. Despite all the atrocities and acts of humiliation of the Israeli officials, the film is about the courage of Palestinians. It is a strong statement against the withdrawal of the Investigation Commission by Kofi Annan and stands tall as a testimony of the terrible times that the Palestinians are living through, day in and out.

What’s cooking in the Study Circle

One should say that the Communist Party dailies of the day were never merely party mouthpieces. On the contrary, they transcended petty party politics. They would grow into being the mouthpieces of the people. Most importantly, they would leave an unmissable imprint on the public sphere of the place. Almost seventy years later, we stand at a time when the mainstream press is dead. Alternative journalism suffers from a lack of resources and ideas. Those who manage to break the shackles of constraints eventually are meant to face the predicament of NewsClick. This incoherent jumbling of thoughts is meant to serve as a reminder for the need to explore possible avenues for innovative journalism. The strikes, lock-outs, and shutdowns seldom feature in today’s press coverage. The reader, too, is reduced to a state of passive acquiescence. Today’s newspapers can seldom make one’s blood boil — as the oppressed stand eradicated from international news, and even worse, are held accountable for voicing their yearning for liberation. It is time that we look back to the past for renewed inspiration.

In this essay, Rajarshi Adhikary explores a little-known Communist Party newspaper archive and thinks about how it could speak to the present-day reader. Our project to translate Rahul Sankrityayan’s Dimagi Gulami is continuing apace. This month, two of our members, Ananyo and Tushar have recovered from the Ashoka Archives of Contemporary India, Prabhakar Machwe’s essay ‘Marxvaad aur Rahul Sankrityayan’, published in a 1985 Karl Marx Memorial Edition of a magazine named Pragya, brought out by the Kashi Hindu Vishwavidyalaya. The essay is currently being rendered into English and will be re-produced as an appendix. This month, however, the study circle in a first, had collectively failed to meet together for a reading session. We are exploring the opportunity to meet in person soon and read DD Kosambi’s autobiographical essay ‘Steps in Science’ (c. 1960), a copy of which can be found here.

Who we are remembering

This month we are remembering the more than twelve hundred Israelis and the more than fifteen thousand Palestinians killed since October 7, 2023.