What we are reading and looking forward to read

State apathy has been a lasting companion of the dying Great Indian Bustard (GIB) and the local villagers of the hamlet called Ganga Ram Ki Dhani in the Jaisalmer district. From this ground-up report by the People's Archive of Rural India, sorrow and anger can be felt looming over the horizons of the Thar desert. The Villagers, who consider the GIB or the godawans as godly symbols, complain that the extremely endangered birds keep dying due to untimely collisions with the high tension wires installed on their lands. In spite of the repeated complaints, state authorities have time and again refused to bat an eyelid. As the reporters rightly exclaim, ‘the dying godawans and their loss of habitat is grimly symbolic of the lack of agency that their pastoral communities have over their surroundings, and the subsequent loss of pastoral lives and livelihoods.’ Squeezed between a nonchalant state and a helpless people, the biodiversity of Jaisalmer continues to march towards a slow death, one godawan at a time, as industrial ‘power’ lurks in search of newer kills.

Peter Linebaugh begins this article on the deep history of the May Day with a rather evocative utterance by John Lilburne — a seventeenth-century English political Leveller: ‘“Murther, murther, murther, murther…”…“M’aidez, m’aidez,” says the international distress signal.’ In this context, the term ‘murther’ alludes to an archaic spelling of murder, standing in for the oppressive circumstances Lilburne endured. Peter Linebaugh astutely draws parallels between the suffering of John Lilburne and the exploitative tendencies of capitalism. He argues that we live in murderous times, marked by ‘an abstraction covering over the four-fold murders of war, famine, pestilence, and neglect.’ In a section titled ‘Maypole and Hydra’, Linebaugh narrates the story of Thomas Morton — an English lawyer and colonist — who arrived in Massachusetts in 1624 with a boatload of indentured labourers. He demonstrates that Thomas Morton and his cohort were wont to lead a liberal and celebratory life. In 1627, they celebrated May Day by erecting a very tall May pole which was eventually destroyed by the Puritans. The celebrations involved dancing, drinking and other activities that the Puritans castigated as immoral. Linebaugh then proceeds to argue that John Lilburne’s advocacy of civil liberties and individual rights was an early fountainhead for the principles and values enshrined in the American Constitution. Lilburne’s own experience of fighting a battle against arbitrary imprisonment and advocating for the rights of the accused also influenced the American Bill of Rights

John Lilburne cried from his prison cell in 1648. “Wherefore unto all you stout and valiant Prentizes [apprentices] I cry out murther, murther, murther, murther.” On May Day 1649 his prison collective published An Agreement of the People, the first democratic constitution. Free-born John Lilburne was a dedicated life-long abolitionist who opposed slavery and prison with equal fervor. As a young man ten years earlier he had to elude anonymous assassins in prison, now with the defeat of his party in 1650, he found it necessary again to call for help in prison conditions of darkness and bad air where murder lay easily in the shadows.

John Williams' biography of C.L.R. James explores both the grey and dark shades of his character. As a young communist during the tumultuous 1930s, James quickly took to Trotskyism. It didn't stop him from admiring the decided Russophiles in Paul Robeson and W.E.B. Du Bois. Sneered at by his Trotskyite comrades as an ‘irresponsible adventurer’, James would go on to establish himself as one of the finest thinkers within their ranks. James' commitment to political praxis was exemplified in his sagacious magnum opus — The Black Jacobins. His account of the Haitian revolution was meant not only to be an exposition of the powerful responses of people to turbulent times, but also serve as a blueprint for future revolutions. Like many of his Trotskyite comrades, C.L.R. James failed to grasp the sheer magnitude of the destruction caused by the Second World War. His sour views on the Soviet Union even during the war years caused many of his peers to question his political commitments. C.L.R. James's life typified the aphorism of ‘unity of opposites’ — a bitter predicament for an otherwise exemplary Marxist. Read more about this book in Gerald Horne’s review here.

We look forward to reading Body on the Barricades: Life, Art and Resistance in Contemporary India by Brahma Prakash, and Suchitra Vijayan and Francesca Recchia’s forthcoming book titled How Long Can the Moon be Caged: Voices of Indian Political Prisoners.

What we are listening to and watching

In this lecture, Stuart Hall ruminates on the enduring essence of Marx’s ideas. He starts by attacking the Marxists who elevate Marx to the level of an infallible, all-knowing demigod, and argues that it is through the destruction of this demigod that Marx emerges on his own. He delineates the broad contours of his lecture: one should read Marx to understand what Aijaz Ahmad calls the ‘logic of capitalism', while simultaneously acknowledging the limitations, contradictions, and inconsistencies of his writings. Although Marx disagreed with the idealist overtones of Hegelian dialectics, Hall argues that he had indeed joined the club of ‘Left Hegelians’. He believed that history was not a static and unchanging phenomenon, rather, an ongoing process propelled by constant conflict and change emerging from inherent contradictions. As time progressed, Marx arrived at the conclusion that the contradictions that moved history emanated from concrete material conditions and not mere ideas. Hall then proceeds to enumerate a few instances where the limitation of Marx’s work becomes apparent, especially in relation to the nature of twentieth-century capital. He also mentions that the propensity of over-enthusiastic Marxists to derive meaning literally from Marx’s theoretical insights is deeply flawed and that Marx would have distanced himself from these so-called ‘Marxists’. He also brings to attention the realities of actually existing socialist states, arguing quite provocatively that Marx had underestimated the deep persistence of the state in an allegedly socialist future.

Among Jana Natya Manch’s most successful plays, Aurat (Woman), remains the most memorable till date. It was written in a single sitting by Safdar Hashmi and Rakesh Saxena in 1979, for the North Indian Working Women's Conference. The bludgeoning edges of patriarchy came under heavy criticism in this play, echoing the emerging feminist movement throughout the country in the 1970s and early 1980s. Marzia Ahmadi Ozkooii’s ‘I Am A Woman’ is recited by all the members of the cast to open the show, which has been performed 2500 times across the urban spaces and hinterlands of India. With Moloyashree Hashmi portraying the titular character, the play navigates the plight of the working-class woman. She is the baby who is rejected once born, the adolescent who is deprecated by her father for attending school and denying marriage, the married damsel who is tortured by the paternal guardian in her conjugal home, and the one who faces rampant sexual harassment at her job interview; emancipated only when she takes a stand, joining the national protests against unemployment. The male characters are seen ‘deflowering’ the isolated woman, always at the center, enabling the reform ‘from within’. This year commemorates 44 years of Aurat, marking a radical display of the persisting precarity of the women’s question. Aurat shows us that ‘naari-mukti andolan’ (women’s liberation) can never be limited to the urban women’s resistance groups alone. Rather, it has to be enacted by the oppressed women outside the purview of the elite society, in domestic as well as public spheres.

What’s cooking in the Study Circle

On entering the Tughlaqabad village, I encountered a post-apocalyptic scene straight out of a dystopian film. The entire area, as far as one could see, was covered with fallen concrete and bricks. This was the Chhuriya Mohalla, which was demolished entirely, without a forewarning on 30th April. The inhabitants of this locality have now been displaced and have lost their homes on which they had spent their meagre savings. While the Supreme Court and the Delhi Government had insisted that the ASI should find rehabilitation measures for these displaced people, nothing has been done so far in that respect. Sumana Roy, a domestic helper, implores that she had no clue that her house was set to be destroyed. She had rushed home from work on getting a call from her husband that bulldozers were in place for their house to be demolished. She found her entire establishment razed to the ground along with all their belongings buried deep within the rubble. This account is not an isolated one but is representative of the predicament of the inhabitants in general. While an ASI notice in January had been served ordering the inhabitants to vacate the place, the BJP MP Ramesh Bidhuri had assured them that no such demolition would take place. On the day of the demolition however, he was nowhere to be seen.

The Tughlaqabad village is populated by people from a variety of religious, linguistic and caste backgrounds, the working-class identity being their common marker. Most of them are migrant labourers dependant on the affluent neighbouring localities of Greater Kailash, C.R. Park and Nehru Place for their livelihood. While the state has termed their settlement as ‘illegal’, the residents claim to have bought the land and the houses they have been living in. Not only have the residents paid for the land, but also an amount of Rs. 10,000 per square feet extra to the local police station and the ASI officers when they built their dwellings. Shabnam (name changed on request) stated that she had to pay a figure of nearly 4 lakhs to the police and ASI officials combined, yet the police officials would frequently barge in and break parts of her house, threatening her to pay up more. The inhabitants have been registered voters holding Aadhar cards against their residential addresses in Tughlaqabad. They regularly paid electricity bills to the BSES with installment plans approved by the company. The boundaries between the spheres of legality and illegality become especially murky when people who were paying thousands to avail ‘legal’ electricity connection and water supply are displaced on grounds of ‘illegal’ encroachment.

Monjima Kar writes about the under-reported plight of the people recently evicted from the Tughlaqabad Village in Delhi, for the Lokayata Blog. We plan to read Niraja Gopal Jayal’s essay ‘The Gentle Leviathan: Welfare and the Indian State’ this month, a copy of which is available on our blog now. The editorial team for our Sankrityayan Translation Project has made quite a bit of progress of late, and we hope to have an edited manuscript ready before the end of June latest.

What we are thinking about

At the outset, the concept of representation presents an intuitively clear and acceptable proposition — in the stead of a large body of different people with disparate views, some person(s) should stand to embody and present the interests and aspirations of this otherwise amorphous mass. As James Madison had put it in The Federalist, these representatives would ideally refine and enlarge the medley of opinions emanating from all within a bounded set — be it an entire nation or smaller institutions like teachers’ associations and trade unions. The core rationale behind this idea is that something is not present physically and consistently, yet present through someone who articulates and deliberates on behalf of many. Here, too, questions of individual autonomy balanced against collective advocacy have come to the fore — Edmund Burke, for example, asserted that representatives should exercise their own judgment and act in the best interests of the nation as a whole, rather than simply mirroring the opinions of their constituents and fighting exclusively for their group aspirations. The establishment of democracy in fits and starts is intimately tied to the gradual and multiple extensions of suffrage to women, the working classes, and racial minorities. That history reminds us that substantive democratic representation arrived much after monarchical governments crumbled to give rise to the earliest representative governments — the usually considered debut of modern Westphalian democracies. However, in its original wellspring in the city-states of ancient Greece like Athens, touted as the earliest and arguably the pinnacle of direct democracy that blurs the line between the rulers and ruled, representation was anything but universal. Being severely constricted, women, slaves, and barbarians enjoyed neither self-agency nor political representation. An interesting parallel can be drawn here with the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when representation was the principal mechanism used by the conservative elites to resist the democratizing impulse of extending universal suffrage, and thereby preventing supposedly chaotic and inept masses from participating in governance.

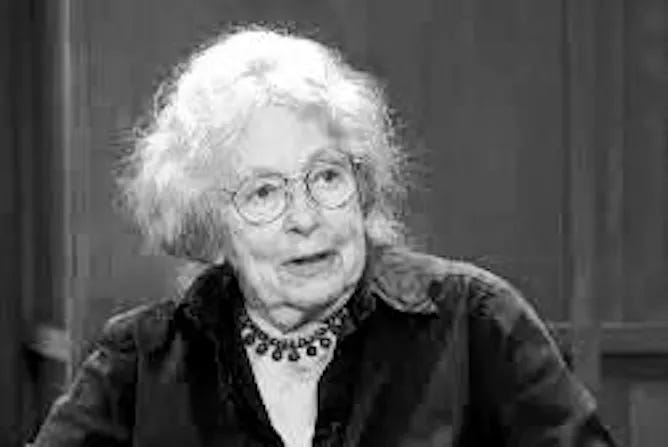

With the rise of technocracy in decision-making, diminishing public participation (and arguably interest) in policy-making, and little regard for accountability apart from and in between elections, a democratic deficit is palpable. This is helped and heightened by neoliberal pressures such as atomisation of individual outlook and pursuits and an economic consensus across mainstream political formations on the imperative of giving a free rein to finance capital and curtailing the state’s role in social welfare. This is indeed a far cry from, notwithstanding its flaws, the collective self-determination manifested in the heydey of the Greek city-states. As the political theorist Hanna Fenichel Pitkin brilliantly puts it, ‘Despite repeated efforts to democratize the representative system, the predominant result has been that representation has supplanted democracy instead of serving it. Our governors have become a self-perpetuating elite that rules — or rather, administers — passive or privatized masses of people. The representatives act not as agents of the people but simply instead of them.’ Despite strains on the central idea of a correlative chain in representation — between the people and the actions and articulations of their representatives, it would be imprudent to discard it completely. Especially when, for the minorities, the symbolism associated with representation — the channel for the articulation of specific interests and grievances — generated and continue to generate a profound sense of empowerment by dint of access to and presence in elusive spheres, otherwise designed to facilitate a tyranny of the majority. It seems that in spite of its many frailties, for this capacity to accommodate alone, the time of representation is yet to be up.

Who we are remembering

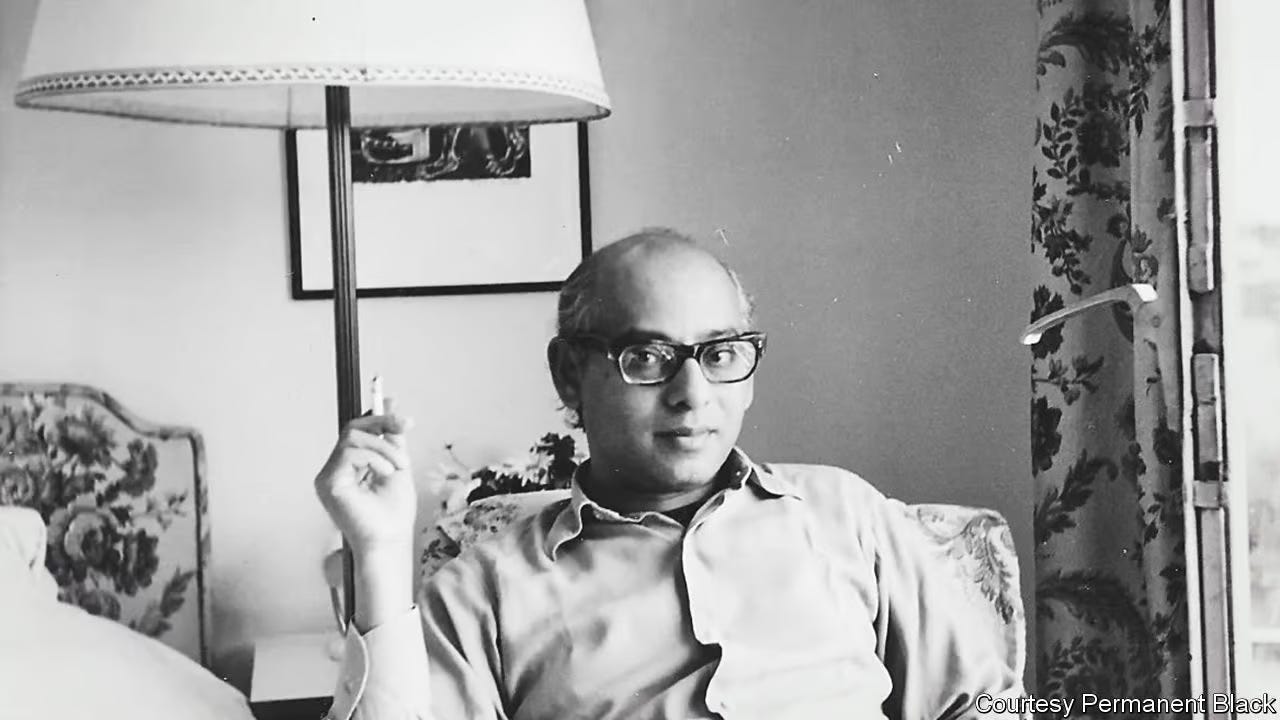

This month, we are remembering the maverick Indian historian and founding editor of the Subaltern Studies, Ranajit Guha, who passed away on April 28th, three weeks short of his hundredth birthday. Read Shahid Amin’s reminiscences about him here.

That’s all from us for now. Let us know what you thought about this newsletter in comments or over email.