What we are thinking about

On April 21, 2024, Prime Minister Narendra Modi gave a speech in Rajasthan in which he described Muslims as “infiltrators” and “those who have more children.” Misquoting former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, Modi said that if the Congress was voted to power, it would “calculate the gold with mothers and sisters, get information about it and then distribute that property…to infiltrators.” “Should your hard-earned money go to infiltrators?” Modi asked. “Do governments have the right to confiscate your property which you have earned through hard work? The gold with our mothers and sisters is not for showing off, it is related to their self-respect. The value of their mangalsutra is not in gold or its price, but is related to her dreams in life. And you are talking about snatching it?”

The above remarks illustrate the affective logic of fascism, which privatizes social issues. Insofar as wealth redistribution demands the restructuring of unequal economic relations, it evinces the dependence of individual wellbeing upon social structures. As long as an alternative economic arrangement is not instituted, the individual will continue to suffer the disempowering effects of destitution. Thus, wealth redistribution mobilizes a negative affect of impotence, wherein individuals realize the impossibility of merely private action and are thus forced onto the path of social cooperation. Hindutva seeks to bypass this problem of social cooperation by asserting the triumphant power of the Hindu militant, who is defined not by the impotence of the present but by the supposed glory of the ancient past. As BJP’s Instagram campaign video that was taken down says, it was precisely because of ancient India’s prosperity “that invaders, terrorists, robbers and thieves used to come again and again, used to loot all our treasures. They used to redistribute the loot among themselves.”

Wealth redistribution no longer functions as a future that will be realized through social cooperation. Instead, it becomes an already-present entity, a pristine past whose shine can be spotted in the illicit enjoyment of the Muslims, in their ‘obscene’ sexuality, for instance. The only thing that is necessary is to defeat the Muslims so that Hindus can regain their lost potency. This mythological imaginary enacts a shift in how we view the economy. Hindutva fetishizes the economy as an unchanging spiritual paradise over which Hindus have proprietorial claim. Modi uses the metaphor of the family to establish a sense of possessiveness: economy is the “gold” held by “mothers and sisters,” a sphere whose sanctity the Congress will violate by converting it into “information” and then using it to “distribute that property”. The economy becomes an ineffable, indivisible entity, which cannot be subjected to any concrete measures. It is an eternal expression of “hard work,” a natural instinct of feminine self-sacrifice that cannot be calculated.

It is evident that fascist affects are deeply gendered, tied to the restriction of women to the category of “mothers and sisters”. This allows the themes of birth, filiation, and genealogy to establish a clear-cut, reproductively pure Hindu community. Anti-fascist action must degender the identity of womanhood: women are not “mothers and sisters” who serve the family but laborers who perform unpaid domestic care work. Work is not an incalculable spirit that remains unchanged but an exploitative relation that is forcibly frozen by the powerful. It consists not of noble “dreams” but social molecules that can be distributed, divided, and destroyed. This can be the premise of a collective, materialist politics.

What we are reading and looking forward to read

Dargahs of Sufi saints have long been sites of syncretic worship. The divinity of the saints is said to live on in their dargahs long after their deaths, and for centuries people from lands far away, regardless of their religion, have visited and prayed at these sites. Dargahs are also a place for communitarian bonding. Apart from praying, they often function as places of rest for travellers, and as gathering sites in villages. Today, dargahs, like so many other symbols of a historically syncretic society, are in danger of being torn down and destroyed. The older generation of villagers across the country recall the days of peaceful harmony between Hindus and Muslims. However, most alarmingly, the present-day youngsters, emboldened by the new wave of Hindutva, petition to bulldoze these sites of worship and attack others for merely posting about medieval or early modern Indian Muslim rulers online. Mosques everywhere, out of the limelight of the media, are being taken over and decorated with saffron flags. Muslim-owned businesses in remote villages are losing loyal customers just because Hindus are too scared to publicly endorse them, and decades-old relationships grow strained in every village. Malgaon in Maharashtra’s Satara district is one of the few villages that have managed to save its dargah from the destructive calls of the ‘brainwashed’ new generation. However, the people who remember the days of unity are quickly being overpowered by the lynch mob of Hindutva. Sadly enough, community, as it was understood before, no longer exists in a lot of Indian villages.

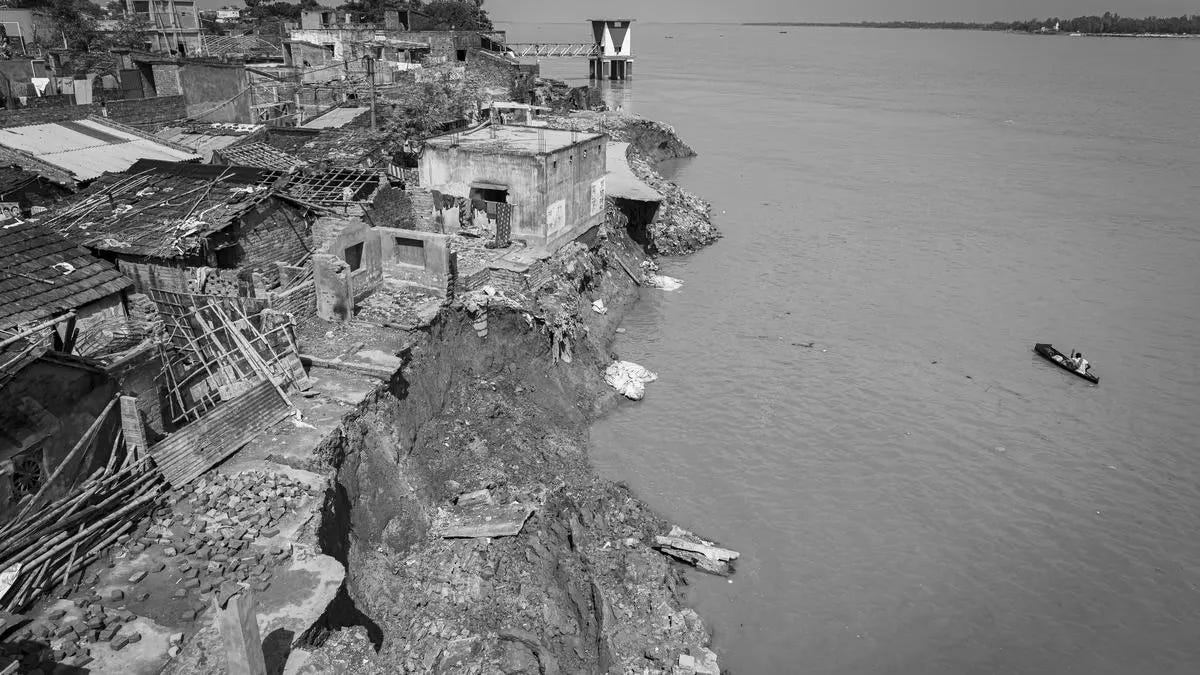

The Ganga causes significant erosion of land in Murshidabad, a district bordering Bangladesh, in West Bengal. Rightly termed as the ‘hungry river’ in this photo story by Sudip Maiti, Ganga relentlessly destroys people's lives and livelihoods, year after year. According to the locals, the construction of the Farakka Barrage has exacerbated the process of land erosion. The barrage, which was commissioned to flush out sediment deposits from the Kolkata Port and revive it in the process, disturbed the natural flow of the river, making the lives of the inhabitants of both sides of the border more precarious. The villages that Maiti visited are inhabited primarily by small farmers and daily wage-earners, who are forced to take refuge in makeshift tarpaulin shelters when the river floods and their houses drift away. The men often migrate to bigger cities in search of livelihood. The women and children have to bear the brunt of nature’s wrath by engaging in hazardous jobs. The photos in the report poignantly depict the sorrows of the affected people from ground zero. Apart from the constant threat of land erosion, these villages are also facing the problem of the river drying up rapidly, endangering the livelihoods of the local fishermen. One may take a look at Sumit Ghosh’s documentary on Dhulian, a small riverine town in the district, and the dried river for further insights.

T.M. Krishna, in his latest article for The Telegraph, talks about how artists carefully select their truths, endorsing beliefs that cater to their deep-seated notions. The artwork derived from and within the milieu of social privilege is created and consumed only by the social elite. The patronizing elite create their own ideas of art and hold them as sacrosanct models before the society. Because of their generational capital, it is the social elite who can afford to take their artistic ventures ‘seriously’ and pursue them professionally. Krishna writes that the status quoist art of the elite does not seek to prompt the audience to reflect upon themselves. The artist, hailing from a marginalized background, on the other hand, creates art which goes the extra mile to show social fissures in a brighter light. Their depictions of their lived experiences become their voices of resistance. The elites are uncomfortable with such art, as it directly challenges their own opportunist politics and gatekeeping practices. They then cry foul about how such art deviates from the normative framework and does not uphold the ‘perfect’ way of doing things — perfection being defined in terms of elite sensibilities of consumption. Krishna calls this phenomenon the ‘sanitization of their work’, which homogenizes the ‘exemplary model’ that conforms to elite establishments, while suppressing true artistic expression at the same time.

We are looking forward to reading Antonio Negri’s A Story of a Communist: A Memoir and Decolonization and Humanism: The Postcolonial Vision of Rabindranath Tagore by Himani Bannerji this month.

What we are listening to and watching

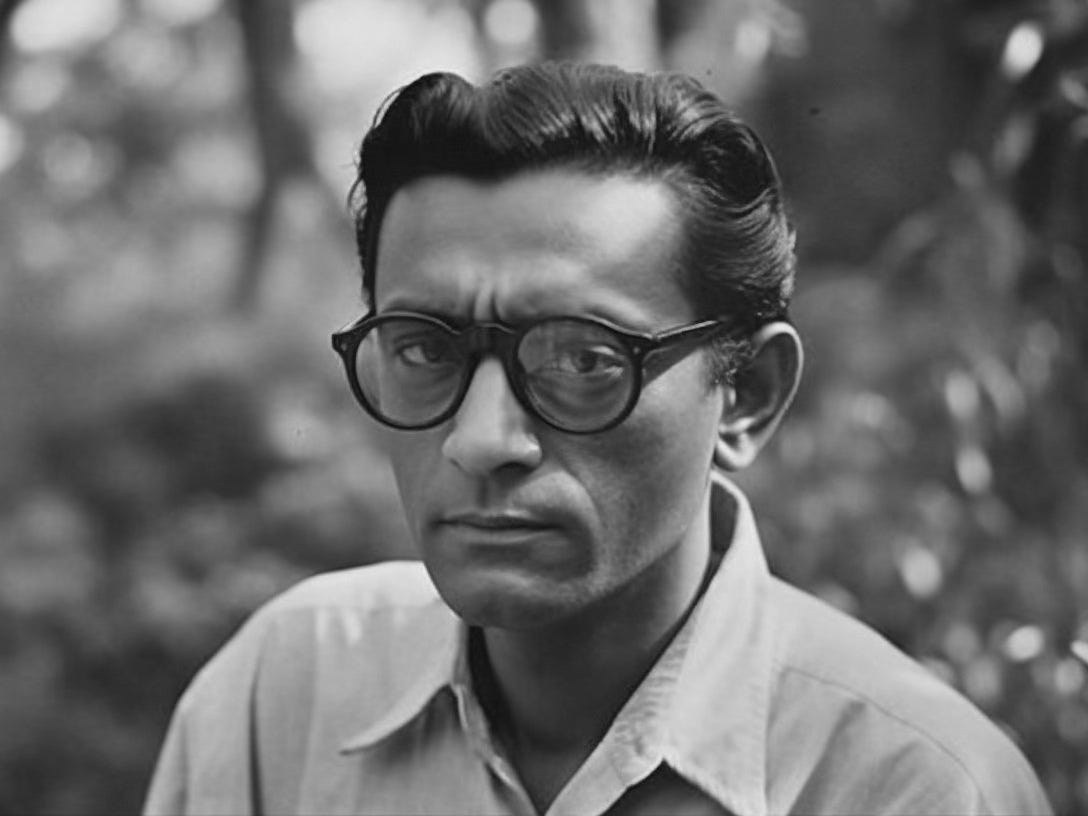

On May 15, 1992, Utpal Dutt gave a speech on Satyajit Ray in a programme organized by the National School of Drama and the Sahitya Akademi after the latter’s demise. Addressing the Indian state’s labelling of Ray as a representative of the ‘Indian Renaissance’, Dutt caustically enquires into the actuality of such a historical movement, when the Hindutva campaign for destroying the Babri Masjid was in full swing. By confining Ray to an already established historical past — namely the legacy of a nebulous Indian Renaissance — the government, notes Dutt, wants “to remove from sight the living contemporaneity of Ray’s ideas and relegate him to a museum of ancient statuary which has ceased to bother us now.” Dutt defines this strategy as one involving “personal adulation for the filmmaker but neglect for, even opposition to, his films.” When one is not busy imposing definite labels on Ray, adequate emphasis can be placed on the sustained labour that his cinematic corpus invites us to undertake. Instead of glorifying him as a man of the Indian Renaissance, Ray’s works indicate the necessity of empowering the masses in the here and now. This involves support for “socially conscious films” against the “gruesome, mindless violence of the commercial cinema”. The Indian state wants to forgo this work of empowerment. That is why it is focused on rhapsodizing about an ‘Indian Renaissance’, when nothing like that exists. Against this status quoist strategy, Dutt foregrounds Ray as “a moment in the conscience of man,” inaugurating a militant morality that defiantly unrolls the consequences of class struggle.

This month, we are watching Johan Grimonprez’s documentary ‘Shadow World’, which aims to inspire activism and political engagement. It is a scathing critique of the global arms trade and the political figures who sustained it, from Reagan to Obama and Blair to Prince Bandar bin Sultan. Based on Andrew Feinstein’s eponymous book, the film uses a mix of interviews and archival footage to highlight the huge volumes of money invested in perpetuating militarization and war. Starting with World War I footage to showcase the wastefulness of wars, the documentary highlights Reagan and Thatcher’s 1980s arms deals with Saudi Arabia, propelling the rise of Saudi political influence. The film underscores how the ruling classes profit from the continuous ‘war on terror’, maintaining it as an indefinite state of global emergency. The director effectively connects historical events, like CIA-backed coups and the Iran-Contra scandal, to their present-day ramifications. Grimonprez does not want his audience to take out their handkerchiefs and wipe tears; he wants them to get out on the streets with their protest signs, their megaphones, and their voting ballots. The ‘Shadow World’, through its clarity and depth, becomes a powerful call to action.

What’s cooking in the Study Circle

In the age of shortening attention spans, memes have the unique ability to attract viewers through small texts and carefully chosen images which attest to and strengthen their inherent cultural prejudices. This characteristic, aligned with the ease with which memes can be created, makes them the perfect medium for the circulation of propaganda among the masses. In such a politically charged climate, it becomes imperative to set forth a counter-narrative to check the infusion of such poisonous ideologies in society. A serious engagement with memes and not brushing them away as merely being products of entertainment can help in a better understanding of the Hindutva forces at play in our society. The creation of memes which offer a secular imagination of India could be one possible way, among many others, to check the proliferation of hatred. Despite the hegemony of Hindutva memes in digital spaces, this step could go a long way in initiating discussions on the pitfalls of constructing India along the template of a Hindu Rashtra.

Supratik Sinha contemplates on the intricacies of the dissemination of Hindutva ideology through memes on social media for the Lokayata blog this month. As promised, notes from our monthly reading sessions will be regularly featured on our digital media pages, most notably on our Instagram handle here:

We have recently started a campaign to raise funds for endowing the annual Satyam Jha Memorial Lecture in perpetuity. If you can, do donate. If not, please spread the word. We rely on your support. Read more about this campaign here.

Who we are remembering

Sadat Hasan Manto was a man of exceedingly clear vision; as a countryman he saw his fellow citizens, as a journalist he saw his country, and as an author he saw the entire world. The details his eye caught continue to surprise us even today — his anguish over the Partition rings true, and his predictions about his new country’s socio-political trajectory stand proven. The humanity he so painstakingly brought out in each of his characters continues to resonate within every reader almost 70 years after his death. Read more about him here.